Park rangers need training and equipment to match the growing threat from sophisticated armed groups

Globally, over 1 000 park rangers have been killed over the last decade. According to the World Wildlife Fund, more than 100 died on the job in Asia and Central Africa in 2018 – nearly half at the hands of poachers. But hundreds more rangers’ deaths in developing countries go unreported, and attacks in the Congo Basin are increasing.

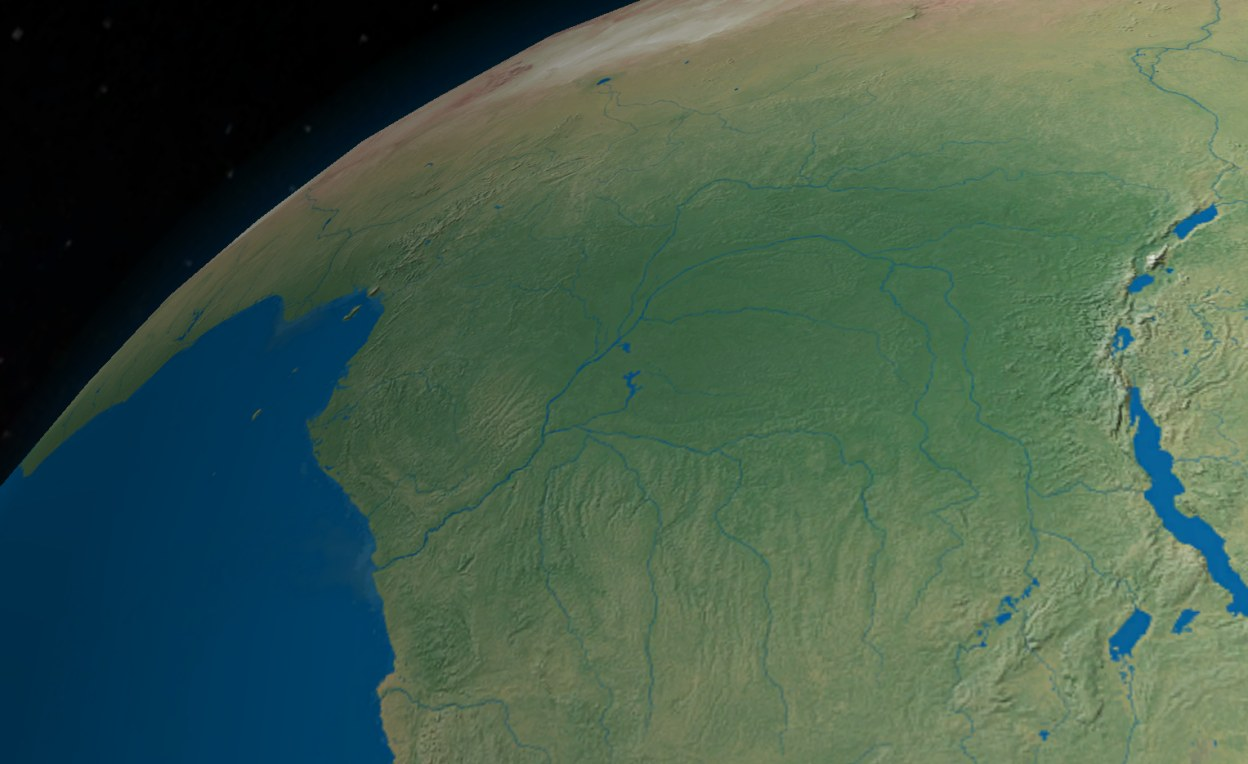

The Congo Basin is home to the world’s second largest rainforest after the Amazon. It spans six Central African countries and has a biodiversity that includes 400 mammal species, 1 000 bird species and 700 fish species. It’s considered the last habitat of the endangered forest elephant, 60% of whose population has been lost to poachers in the past decade.

Dozens of national parks in the Congo Basin have a rich array of wildlife such as endangered bonobos, leopards, bongos, African golden cats, tree pangolins and African slender-snouted crocodiles. As poachers push some wildlife to the brink of extinction, the parks’ ecosystems are under threat.

Park rangers in the Congo Basin play a vital role in safeguarding its forests, wildlife and natural resources. They patrol protected areas, keep track of water levels in rivers and lakes, manage fires and search and care for animals in distress. They also help communities manage human-wildlife conflicts, monitor wildlife populations and track and intercept illegal activities. Rangers work tirelessly under difficult conditions that include threats of injury and death from wild animals, poachers and villagers.

The global illicit economy in wildlife products is estimated to be worth more than US$20 billion a year, ranking fourth in value after drugs, weapons and human trafficking. Research suggests that US$25 million is lost to African countries every year as a result of elephant poaching alone. Efforts to cut this illicit economy put African park rangers in the crossfire of poachers.

Many armed groups have bases in and around Virunga National Park and attack rangers with military weaponsLocal communities’ anti-park sentiments also put park guards at risk. Conflicts arise over park boundaries and land appropriation. Regulations covering the use of natural resources also restrict locals from using park areas for agricultural purposes. Armed groups – many of which have links to these communities through family and other social ties – use these conflicts to garner support in areas where they operate and engage in poaching.

Since 2010, recorded attacks on park rangers in the Congo Basin have been rising, especially in Lobéké, Garamba, Kahuzi-Biega and Virunga national parks. Research by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) Project shows that attacks were sporadic a decade ago, but are slowly rising. The ACLED data relies on local groups and media reports, and many incidents probably go unrecorded.

Virunga National Park has become a hotspot with over 100 of the park’s team of 700 rangers murdered in recent years. In 2014, unknown shooters wounded internationally renowned Belgian conservationist Emmanuel de Merode, the park’s director. In 2018, the park was closed for eight months after a female park ranger was killed and two British tourists and their driver kidnapped. Twelve park rangers died in attacks by poachers in 2020 and another nine in 2021, including six eco-guards from the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature.

The illicit trafficking of wildlife and natural resources finance and sustain armed groups' operationsThe attackers include local terror groups such as the Mayi-Mayi militia, M23 rebels and unidentified armed bandits, as well as insurgents with transnational reach in Central Africa and neighbouring countries. These include the Lord’s Resistance Army, Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda and Islamic State West Africa Province.

Many of these insurgents have set up bases in and around Virunga National Park, and attack rangers with military grade weapons. The illicit trafficking of wildlife products (including elephant ivory, rhino horn, game meat, bones and skins), as well as other natural resources (such as minerals, timber and charcoal) finance and sustain the terrorist operations. According to a coalition of environmental and human rights organisations, armed groups earn hundreds of thousands of dollars each month this way.

An Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux du Gabon (ANPN) official, who spoke to the ENACT project on condition of anonymity, notes that terrorists from West, East and Central African countries are invading Gabon’s forests, where they attack rangers and steal their weapons.

Due to the extreme danger facing rangers, training must incorporate paramilitary drills and surveillancePrioritising the safety of park rangers is becoming essential due to the rising number of attacks. Solutions lie in adequately resourcing ranger squads and improving training to match the current demand and dynamics of the poaching war. Due to the extreme danger facing rangers, training must incorporate paramilitary drills, covert and aerial surveillance, crime scene management and community relationship building for intelligence gathering.

Considering the sophistication of the armed groups and poachers, governments must also improve the weapons available to rangers. Recently in Cameroon, soldiers were deployed to help park rangers – a tactic that other Congo Basin countries could follow. A multinational joint task force among the Congo Basin countries – all of whom are members of the Central African Forests Commission – is another viable solution that must be explored.

‘We have to really collaborate to win this war,’ says the ANPN official. ‘Bilateral and multilateral cooperation is very important.’ Congo Basin member states have a duty to protect the lives of those who guard their forests against external assailants, including terror groups and armed poachers.