Authorities in Mali seem to be considering negotiations with Jamaat Nusratul Islam wal-Muslimin, the country’s largest Islamist insurgency. Pursuing talks will be a tall order, given the stakes and the group’s al-Qaeda connection. Both the government and the militants should begin with incremental steps.

Principal Findings

What’s new? The Malian government has expressed willingness to explore dialogue with Islamist insurgents, some of whom have sent reciprocal conciliatory signals. Previous talks among communal leaders, militants and militiamen yielded several local ceasefires that eased suffering in rural areas. Yet no one has taken steps to prepare high-level negotiations.

Why does it matter? Thousands have died as Mali’s conflict grinds on. Both the army and the jihadists are taking increasingly heavy losses, but neither party appears capable of securing military victory. Ethnic violence is spiralling. Foreign partners are showing signs of exasperation with the country’s interlocking security and political crises.

What should be done? The Malian government and those jihadists who have said they will talk should strengthen their commitment to dialogue. Ideally, to this end they would defuse resistance among elites and foreign partners, appoint negotiating teams and possibly even agree on a mediator.

Executive Summary

Both Mali’s government and the country’s largest jihadist grouping, Jama’at Nusratul Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), say they want to talk about ending their bloody conflict. Yet neither party has taken steps to make dialogue happen. After eight years of fighting, the government and its external partners lack a convincing military strategy for concluding the war. Talks could allow the government to cut deals with jihadists that would save lives. But officials face major obstacles, not least their own division over the notion of such negotiations. France, Mali’s most important ally, opposes dialogue. JNIM, meanwhile, says foreign forces must withdraw before it will talk, deepening the other side’s reluctance to engage. But with rural militias proliferating and elite squabbles prompting two coups in 2021 to date, the demoralised public is swinging behind dialogue. So as not to rush into talks unprepared, the government and JNIM should first unify their ranks and think through their positions on key issues, particularly the role of Islam in state and society. They should also name negotiation teams and agree upon a mediator.

JNIM is a coalition of four jihadist groups formed in 2017 that operates from rural strongholds scattered throughout northern and central Mali. It is an al-Qaeda affiliate, but most of its constituent elements are under Malian command. For a time, JNIM made significant headway in capturing territory, but the conflict appears to have reached an impasse, with both sides inflicting and incurring heavy losses. The coalition nominally seeks to impose its ultra-conservative interpretation of Islam on both state and society. In practice, however, the militants have thus far adopted a largely pragmatic approach, ruling through a system of shadow governance that allows for a degree of local autonomy. They have also agreed to ad hoc ceasefires with self-defence militias. These agreements secured at least a temporary lull in combat in several areas.

” For years, the [Malian] government nixed the idea of dialogue with militants, but lately it has begun rethinking. “

For years, the government nixed the idea of dialogue with militants, but lately it has begun rethinking its opposition due to bad news from the front and political instability in the capital. Early in 2020, following an outcry over unprecedented mass killings of civilians and soldiers, then President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta said he was ready to engage with militants. JNIM responded positively within weeks. The junta that ousted Keïta in a coup a few months later named a civilian prime minister, Moctar Ouane, who spelled out ways to pursue dialogue in the government’s action plan. The coup makers removed Ouane, too, in May 2021, but his successor must still contend with a public that has become dissatisfied with the purely military approach to dealing with insurgents. Foreign partners have grown impatient with Mali’s political turmoil. France, for its part, announced that it will reduce its military footprint in the Sahel and hand over responsibility for the anti-jihadist fight to the European Task Force Takuba. Meanwhile, Malian politicians, activists and religious leaders are bickering over how to resolve the conflict.

Talks are by no means guaranteed, and, if they do happen, are unlikely to bring immediate relief to a suffering Malian population. Many politicians, civil society representatives and religious leaders harbour deep reservations. The concerns are widespread, even among Malian officials who have helped shape dialogue policies in recent years. JNIM leaders, while showing an interest in talking, are hard to pin down about what compromises they might accept. France’s rejection of dialogue with JNIM’s top leadership – in the words of French officials, those “responsible for the deaths of thousands of civilians and … Sahelian, European and international soldiers” – poses another challenge. Finally, and most importantly, neither the Malian government nor the jihadists have determined what they want to talk about and how or where such talks could take place. Yet, as it becomes obvious that the conflict has no military solution, the government could at least begin exploring engagement with militants as part of its search for an alternative way forward.

To this end, the Malian government and the jihadists can take steps to bolster their commitment to peace talks. Malian authorities should seize upon fatigue with the anti-jihadist fight as an opportunity to take the lead in promoting efforts toward a political settlement. Four concrete measures could render dialogue a more viable option:

The Malian government and the jihadists should work to overcome suspicions of dialogue within their respective ranks. The government will need to engage in shuttle diplomacy to convince sceptics, in particular France, that engaging with JNIM is worthwhile, given the flaws of existing policy. The Malian authorities should reassure foreign partners that a settlement with JNIM will entail at least the latter’s commitment not to attack foreign interests in Mali or use Malian soil to plot attacks abroad. In addition, the government should get the insurgents to pledge that, to the extent possible, they will stop other militants from carrying out such attacks.

The government and JNIM’s leaders can signal their seriousness about talks by appointing credible, inclusive negotiating teams. Neither the government nor JNIM has said who might represent it at the table. Designating teams could kickstart the process. The teams could define strategies, set the agenda for talks and conduct negotiations at a later stage.

Before embarking on talks, the Malian government should facilitate a public debate on the role of Islam in state and society, which could help draw the contours of possible compromises and trade-offs between authorities and the JNIM leadership. Both sides should then use the outcome of this debate to think through their own positions before entering talks.

Dialogue between the government and jihadists is likely to encounter obstacles that a mediator will have to help them surmount. The two sides will need to agree upon a trustworthy third party, ideally a neutral country with experience in facilitating similar negotiations, to serve in this capacity.Dialogue is worth pursuing, notwithstanding enormous challenges. The gap between the two sides’ positions is yawning, and the task of negotiating a comprehensive settlement may seem impossible. Just talking to militants may seem a tall order, politically speaking, given some of their stated goals and their al-Qaeda connection. Even if JNIM has shown some pragmatism while fighting an insurgency, it is unclear whether that would extend to compromises off the battlefield. Many Malians oppose its draconian interpretation of Islam. But the present approach is clearly not working: without a change in tack, civilians in much of the country will remain caught up in a violent struggle between militants and security forces. The incremental steps outlined above could pave the way to at least exploring whether a negotiated settlement is a feasible option, and the cost of finding out would not necessarily be steep. Given the worsening instability wracking much of Mali, these steps are at least worth a try.

Bamako/Dakar/Brussels, 10 December 2021

Introduction

The war in Mali is at a crossroads. Locked in a mutually hurting stalemate – at least as long as Mali’s foreign partners maintain their military presence – the Malian government and leaders of the jihadist coalition Jama’at Nusratul Islam wal Muslimin (the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims, or JNIM), have expressed cautious interest in negotiations as an alternative to settling their conflict by military means. After eschewing talks for years, former President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (2013-2020) changed tack in February 2020, saying his government would “explore the path” of dialogue with jihadists.

A few weeks later, JNIM issued a statement welcoming the decision, albeit conditioning its engagement on the withdrawal of foreign troops from Mali. Following Keïta’s ouster in an August 2020 coup, Mali’s interim government has sent mixed signals on prospects for dialogue. Both the Malian authorities and jihadist leaders had previously rejected talks as a matter of principle.

The sides’ apparent willingness to talk is a positive step, but domestic and international support for negotiations is far from guaranteed. Malian secular elites, Sufi Muslim scholars and human rights activists have expressed concern about dialogue with jihadists, whose vision for the country contravenes Mali’s secular constitution.

France, which leads anti-jihadist military operations in Mali but plans to almost halve its troop deployment, rejects negotiations with jihadist leaders.

If they do engage in talks, the Malian government and jihadist leadership would be entering uncharted territory, having taken no concrete preparatory steps. Both sides risk alienating allies. Furthermore, neither party has determined how to conduct negotiations, what they want to talk about or, most importantly, which compromises they might be willing to accept in seeking a political settlement.

This report is part of a series exploring policies aimed at curbing jihadist violence in central Sahelian countries. In particular, it builds on a 2019 report that gauged the possibility of dialogue with militants in central Mali.

While the previous report focused on the Katiba Macina, one of JNIM’s members, this report analyses prospects for dialogue between the Malian government and JNIM’s Malian top commanders. The report takes as a starting point that both state officials and jihadists have shown openness to talks. Its primary goal is thus not to convince the parties to engage in dialogue with one another. Nor does it provide a roadmap of how they can conduct negotiations, as these details must come later. Rather its aim is intermediate: to get the protagonists to move from manifesting an interest in dialogue to creating the conditions wherein talks can actually take place.

The report looks solely at Mali and only at options for talking to JNIM rather than other militants. It is in Mali where JNIM’s presence is largest and the fighting between it and government forces fiercest. Malian officials have also publicly acknowledged that they would consider dialogue with JNIM’s leadership. Though JNIM is active in Niger and Burkina Faso, its objectives in those countries are less clear than in Mali and prospects for talks with its leadership much slimmer.

Although JNIM is not the only jihadist group in Mali, so far Malian officials view it as their only possible militant interlocutor. They exclude the second biggest group, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), because until recently its leaders – its top leader Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui was killed in a French airstrike in August 2021 – were foreigners and its combat tactics particularly brutal. ISGS leaders, for their part, have expressed no interest in talks, either.

The report is based on dozens of interviews with Malian officials, diplomats, and current or former JNIM members and their associates, conducted in Bamako, Kidal and Mopti, Mali; Ouagadougou and Soum, Burkina Faso; and Niamey, Niger between 2019 and 2021. It also incorporates dozens of JNIM’s text and audio statements.

II. JNIM: Rise of a Malian Jihadist Coalition

In March 2017, four Mali-based jihadist groups – Ansar Dine, the Katiba al-Furqan (the Saharan branch of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), the Katiba Macina and al-Mourabitoun – came together to form the JNIM coalition.

Three of these groups had their origins in the 2012 uprising in northern Mali, while al-Furqan had emerged earlier, in the 2000s. United by fealty to the al-Qaeda network, the groups distinguish themselves from other militants who have pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. JNIM has since become the largest jihadist force in the central Sahel.

A. A Jihadist Coalition

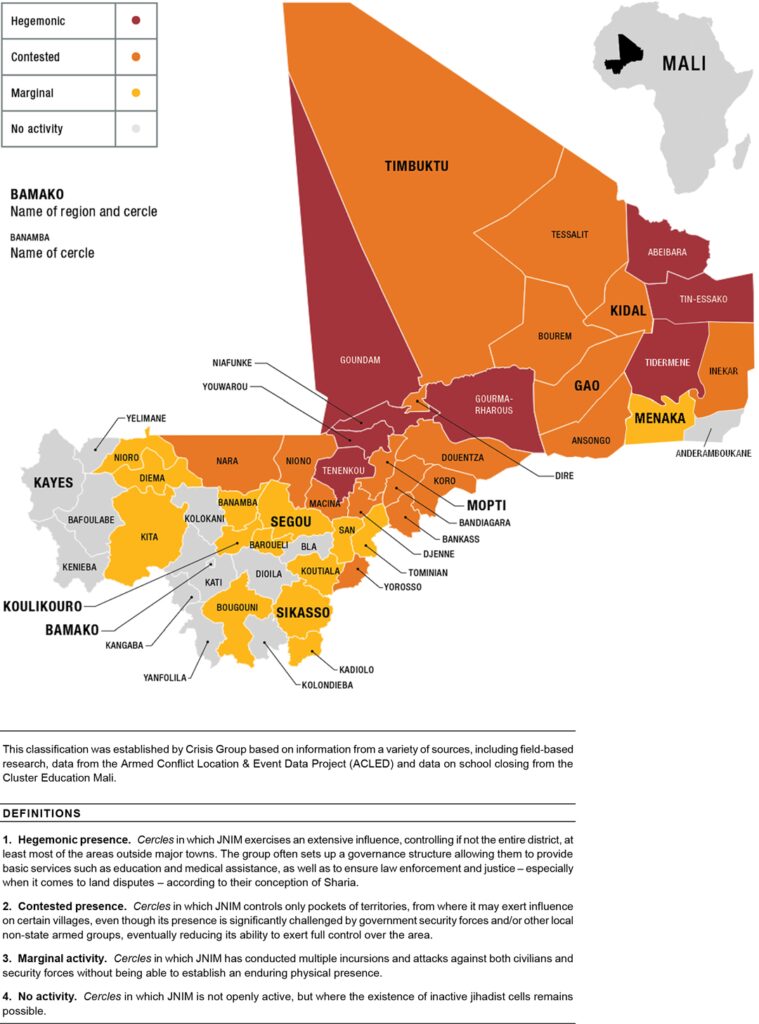

The four katibas (“battalions”, in Arabic) operating under JNIM’s banner already had strongholds throughout northern and central Mali: Ansar Dine in northern and eastern Kidal, the Katiba Macina in the Mopti and Segou regions, al-Furqan in northern and western Timbuktu, and al-Mourabitoun in south-eastern Timbuktu and northern Gao. Since 2017, JNIM has consolidated its influence in these areas, expanded into neighbouring Burkina Faso and stamped its footprint on spaces in southern and western Mali as well as in western Niger. Furthermore, the coalition has staged attacks in northern Côte d’Ivoire and Benin, signalling its intention to encroach on Gulf of Guinea countries.

Iyad ag Ghaly (born in 1954) a Tuareg rebel turned jihadist, leads the coalition.

His experience as a military strategist, and a deft negotiator in previous talks with the Malian government, has bolstered his reputation among Tuareg in northern Mali and beyond, in turn helping cement his authority in JNIM. His leadership appears uncontested and, if anything, has grown stronger of late due partly to his achievements. Another reason is that several senior commanders and other potential rivals in the coalition have perished. Under his command, the various katibas tightened their coordination and improved communication, enabling them to extend their reach. Ag Ghaly’s headquarters is believed to be situated in his native Kidal region, near the Algerian border.

” JNIM’s decentralised governing structure gives the ‘katibas’ significant leeway to run their own operations. “

JNIM’s decentralised governing structure gives the katibas significant leeway to run their own operations. Katiba commanders therefore wield considerable influence, too. Among the coalition’s other main figures are Hamadoun Koufa, leader of the Katiba Macina; Abderrahmane Talha (known as Talha al-Libi), head of the Katiba al-Furqan; and Sedane ag Hitta, an Ansar Dine commander.

All these leaders are Malian and primarily operate from Mali, with the exception of al-Libi, whom, despite his name, observers describe as Mauritanian though his mother might be Malian. Foreign jihadists with key roles in JNIM have included Algeria-born Djamel Okacha (also known as Yahya Abul Hammam) and Morocco-born Ali Maychou (also known as Abderrahman al-Sanhadji), who served as the coalition’s chief qadi (“judge”, in Arabic). French airstrikes killed both men in 2019.

While JNIM has pledged allegiance to Algeria-based al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Taliban and al-Qaeda General Command, it is unclear whether they are subordinate to foreign networks.

There is no doubt that AQIM has had a large influence on JNIM. AQIM commander Abou Obeida Youssef al-Annabi describes JNIM as an “integral part” of AQIM, which in turn is an “integral part of al-Qaeda”. Al-Furqan is seen as an AQIM branch, and it has numerous foreigners in its ranks, including fighters from Algeria and Mauritania. AQIM pioneered jihadism in northern Mali, serving as an incubator for some of the Sahel’s first jihadist leaders – ag Ghaly, for instance, converted to jihadism under the influence of AQIM commanders. As early as the insurrection’s start, however, the Sahelian jihadists appeared to form their own katibas against the wishes of AQIM and al-Qaeda General Command, which had instructed them to not wage war upon Sahelian states.

Thus, they may act with a degree of autonomy vis-à-vis AQIM and al-Qaeda.

B. JNIM’s Strategy

In its statements, JNIM says it pursues two main goals: the withdrawal of foreign troops and the establishment of Islamic rule, primarily in Mali, and potentially in the entire Sahel.

By Islamic rule, its rhetoric suggests, it aims to bring Mali’s political system as well as social practices in line with a particularly stringent interpretation of Islamic law or Sharia. The coalition rejects the country’s constitution as un-Islamic and the principle of secularism enshrined in Malian law as illegitimate. It describes electoral democracy as the rule of ignorance (hukm al-jahiliyya) as opposed to the rule of God (hukm Allah).

As outlined below, the militants envision a society where people adhere to a code of conduct that restricts choices in terms of clothing, entertainment and education and limits interactions between men and women, among other things. But while JNIM’s rhetoric suggests a rigid commitment to global jihadist ideology, its approach to applying the rules it touts in official communications has been pragmatic.

In order to achieve its goals, JNIM relies on four policies: first, to spread over the largest possible geographical area; secondly, to exhaust the army and security forces by attacking them continually; thirdly, to gain popular support; and finally, to adopt the principle of guerrilla warfare while also using regular military tactics when possible.

To impose their rule, militants have used both persuasion and coercion. JNIM issues a broad array of statements proclaiming the righteousness of the jihadist vision. The group’s dedicated media outlet, al-Zallaqa Media Foundation, regularly publishes these statements as well as video and audio recordings of speeches to claim responsibility for attacks or to spread its ideas. But the jihadists have also sought compromise with residents in places they control, maintaining traditional power structures and allowing local officials to manage daily affairs on militant’s terms.

Still, the jihadists often resort to individual or collective punishment of those who resist their rule. They have surrounded villages that host military bases, blocking the movement of people and goods and interrupting access to farms to impose their will.

For example, Katiba Macina fighters maintained a six-month blockade on several villages, including Farabougou, in the south-central Segou region, between October 2020 and March 2021.

” JNIM militants often strive to provide services to locals. “

In areas under their control, JNIM militants often strive to provide services to locals, including Islamic courts and protection from crime, as well as price regulation and quality control in rural markets.

Jihadists have tried to be responsible stewards of natural resources, in some cases stopping villagers from cutting down trees. They have also allowed humanitarian NGOs to supply health care, veterinary services, potable water and food. At the same time, they have closed hundreds of government schools, which they perceive as contravening Sharia, primarily because boys and girls mix in the classroom and the schools do not teach Islamic courses. Instead, they encourage residents to enrol children in Quranic schools.

JNIM also collects zakat – the alms that Islam requires from wealthy Muslims.

Militants use some of this money to finance their activities and, in some places, redistribute the remainder to people in need. While zakat is burdensome for those whom the jihadists tax, presumably based on their riches, the redistribution of wealth is one of the aspects of jihadist governance that poor people appreciate the most.

C. Sharia Enforcement: Between Ideology and Pragmatism

The forcible imposition of Sharia is the most striking, and often controversial, aspect of JNIM’s governance. In areas under JNIM control, a strict interpretation of Islam rules most of public life, and the group’s ultra-conservative rules have drastically altered people’s behaviour.

The dress code and the ban on the mixing of sexes (except for married couples or siblings) in public transport such as taxis, boats or donkey carts have been a particular burden on women, who find it difficult to farm, travel or trade in rural markets. In central Mali, the jihadists’ propensity to whip women who are not wearing a hijab or niqab is a major cause of anger among villagers.

The extent to which jihadists enforce Sharia varies, however, as they rely on a system of shadow governance that has kept local hierarchies largely intact.

They rarely stay in the villages they control but establish a base – known as a markaz (“centre” or “camp”, in Arabic) – in a remote area and leave local notables to run daily affairs, though on JNIM’s terms. This decentralisation has led to a degree of flexibility in enforcement of JNIM’s rules. For instance, residents of several JNIM-controlled areas were able to vote in the 2018 elections, despite the group’s rejection of electoral democracy. That said, JNIM militants have also been responsible for killing or persecuting local notables who have resisted their rule.

” [JNIM] insurgents seem aware that violent enforcement of Sharia might aggravate frictions with locals. “

For the most part, insurgents seem aware that violent enforcement of Sharia might aggravate frictions with locals, most of whom are Muslim but do not subscribe to JNIM’s interpretation of Islamic law. For this reason, perhaps, JNIM has not enforced the most callous provisions found in self-described Islamic penal codes, such as stoning of convicted adulterers or cutting off hands of thieves.

The organisation has also shown itself to be amenable to compromise. In the Kidal region, complaints of abuse by the hisba, or moral police, convinced local leaders to soften requirements. JNIM has justified this easing by saying locals are not ready to accept all the punishments in Islamic law. Many ideologues, including ag Ghaly, have advocated for a moratorium on enforcement of some aspects of JNIM’s codes on the grounds that Muslim societies are not religiously mature enough to embrace these sanctions.

The ability to navigate local culture has allowed JNIM militants to entrench themselves. From late 2019 onward, for example, JNIM began to increasingly involve residents in local affairs.

In many parts of northern Kidal and in central Malian districts, JNIM militants allowed villagers to name their own qadis from among local religious leaders, who could draw on jurisprudence used in the past. Restrictions gradually loosened, notably the school ban, with some local qadis giving non-Quranic schools permission to reopen on certain conditions. Still, the collaboration between jihadists and local qadis is often fraught with tension.

III. Local Dialogue Initiatives

Dialogue has become a viable option as the conflict appears to have reached an impasse, though JNIM has made significant headway in capturing rural areas. As both parties hesitated to engage in high-level talks, they trained their sights on local dialogue to stem the violence and build peace from the ground up.

A. A Mutually Hurting Stalemate

The conflict between the Malian state and JNIM is locked in a stalemate as neither side appears capable of achieving military victory. Bamako struggles to contain the insurgency despite the efforts of Malian troops, the G5 Sahel joint forces, the French Barkhane mission and, more recently, the European Task Force Takuba. The UN peacekeeping mission in Mali, MINUSMA, while not a counter-terrorism force, has also frequently clashed with JNIM fighters.

Military operations have yielded mixed results. True, they have inflicted heavy losses on JNIM, but thus far they have failed to quash the coalition or secure zones that they have retaken from the militants. While the military often focuses on holding major towns, the jihadists often retreat to hideouts in the bush, desert or mountains, from which they continue to launch periodic raids. As a French diplomat put it, counter-terrorism operations in the Sahel are comparable to “mowing a lawn, only to see the lawn grow again after a little while”.

” France, the driving force of foreign military efforts in the Sahel, is showing battle fatigue. “

More critically, France, the driving force of foreign military efforts in the Sahel, is showing battle fatigue. As the French public’s support for these efforts plunged, President Emmanuel Macron announced in June 2021 that he would close three military bases in Mali and reduce the number of French troops in the region to between 2,500 and 3,000 as part of an overhaul of French military presence (see Section IV.C).

By November, French soldiers had withdrawn from Kidal and Tessalit, two remote military bases in the north near the Algerian border.

On the other side of the coin, even as JNIM has gradually expanded its reach, it has lost hundreds of fighters and several senior commanders. Despite unrelenting attacks, JNIM has won complete control of only a few districts (or cercles) in northern and central Mali, occupying mainly rural areas outside major towns (see the map of JNIM’s presence in Mali below).

Three of the five leaders who formed the coalition in 2017 have perished, most in French airstrikes, while a fourth, Hamadoun Koufa, narrowly escaped a bombing in November 2018. Despite its extended reach, JNIM is unlikely to prevail over its enemies and compel all foreign troops to withdraw in the near future. As Western and other powers continue to pour vast sums into the region’s security sector, whether by boosting the European force or deploying drones, Mali’s conflict now resembles a war of attrition.

Furthermore, JNIM now has to contend with an array of armed groups seeking to dislodge it, including from its strongholds. The jihadists’ recruitment strategies sharpened intercommunal tensions, which in turn motivated thousands of villagers to organise themselves in self-defence. In most cercles where JNIM’s offshoots operate, security forces and non-state armed groups fighting for various agendas, including separatists, loyalists, bandits and ethnic militias, challenge the militants’ territorial control. The civilian death toll, meanwhile, has climbed exponentially. Since the crisis began in 2012, over 11,000 people have died, more than half of those in the last two and a half years alone.

Growing communal violence has also undermined JNIM’s ability to rally Malians behind its cause. As insecurity surged, sedentary farmers increasingly directed their anger at ethnic Fulani herders, whose strong representation in jihadist fighters’ ranks gave an ethnic dimension to some JNIM offshoots.

These tensions hindered the group’s expansion as it struggled to find new recruits among rival ethnic groups. In some instances, fighters temporarily left their bases to protect their home villages, pointing their guns at militiamen or civilians instead of the “infidel” government.

Competition with ISGS poses another challenge. Fighting between JNIM militants and those affiliated with ISGS has escalated. After coexisting in the central Sahel for years, al-Qaeda and ISGS fell out in mid-2019 as the latter encroached upon JNIM strongholds in northern and central Mali as well as northern Burkina Faso.

Disagreements over access to land and pasture heightened tensions, culminating in major clashes between the two groups from early 2020 onward, particularly in central Mali, the Gourma area, and northern and eastern Burkina Faso. JNIM’s willingness to speak with the Malian government also widened the gap between the two rivals.

” [The Taliban seizing power in Afghanistan in August 2021] has resonated among JNIM’s leadership. “

All that said, the turn of events in Afghanistan in August 2021, when the Taliban took advantage of the U.S. departure to seize power, has resonated among JNIM’s leadership. While the two insurgencies’ trajectories are markedly different, the Taliban’s sweep across Afghanistan will likely reinvigorate militants in Mali. On 10 August, five days before the fall of the Afghan capital Kabul, ag Ghaly published a triumphant message labelling Barkhane’s restructuring a victory for JNIM while congratulating the Taliban on “the historic withdrawal” of U.S. troops.

Moreover, the Afghan debacle highlights the limits of counter-insurgency efforts that rely on foreign troops. In its statements, JNIM attributes that withdrawal to the Taliban’s “ferocity in combat”. At the same time, JNIM leaders appear to have noted that the Taliban achieved its main goal not just by fighting but also by talking, in the Taliban’s case to U.S. diplomats. So far, a similar model – talking directly to France about a French pullout – is off the table in Mali, but the value of using diplomacy alongside force seems, for JNIM, to have hit home.

B. Local Ceasefire Accords

As ethnic violence surged, the protagonists have tacitly encouraged talks among local JNIM offshoots, communal leaders and self-defence militias to calm tensions. Communal leaders and mediation NGOs often led such initiatives.

While the Malian government took part in some negotiations by sending emissaries and supporting mediators, it did not sign any agreements.

Most negotiations focused on protecting civilians, facilitating the return of displaced persons, lifting jihadist blockades and clearing checkpoints to allow locals to reach their farms or travel to markets.

Emblematic of these talks is the “Niono agreement” between jihadists affiliated with the Katiba Macina and self-defence militias called donso (“hunters”, in Bambara). Starting in October 2020, Katiba Macina militants placed several villages in the Niono district (Segou) under siege, accusing the inhabitants of collaborating with the government. The Malian army tried and failed to liberate one of the villages, Farabougou.

This defeat paved the way for talks between jihadists and the donso, facilitated by emissaries from the High Islamic Council of Mali and supported by the junta in Bamako. At first, the two parties put forward seemingly irreconcilable demands. After several months of direct talks, however, in March 2021 delegates agreed to a ceasefire pausing the six-month siege. Fighting resumed in September, with each side accusing the other of disrespecting the agreement’s terms.

The Niono agreement illustrates the evolving dynamics of local peace talks between JNIM offshoots and ethnic militias.

Since 2017, over a dozen similar initiatives have taken place involving JNIM bands and residents in northern and central Mali. In 2017, community leaders in Kidal brokered talks between Ansar Dine and members of a squad affiliated with the Tuareg separatist Movement for the Liberation of Azawad that participated in French counter-terrorism efforts. The talks resulted in a non-aggression pact that significantly calmed tensions in the region.

Similarly, in central Mali, JNIM affiliates, on one side, and Dogon and Bambara militiamen, on the other, signed several peace deals, including in Ké-Macina in 2019, and in Koro, Bandiagara and Niono in 2020 and 2021.

These local ceasefires decreased violence against civilians, particularly in central Mali, where attacks on villagers have dropped substantially in some areas since June 2020.

Whereas previous intercommunal dialogue initiatives failed partly because mediators excluded jihadists as interlocutors, the recent accords have succeeded, to some extent, partly because they included jihadists.

But they have been unsatisfactory in other ways. Some accords only temporarily halted the violence. For instance, fighting between donso militiamen and jihadists resumed a few months after they signed the Niono agreement. Moreover, despite accords saving civilian lives, jihadists have been the main beneficiaries. Militants have often used ceasefires to extend their authority.

They ask residents not to interfere in the conflict, a means of isolating them as well as self-defence groups in the area from the government officials and security forces that are supposed to protect civilians. Militants usually assert that their jihad is directed solely at the state and that they will spare civilians who do not collaborate with the government. (In reality, however, JNIM militants have killed hundreds of civilians, mainly during communal violence in central Mali. ) As the local ceasefire agreements remain fragile, the belligerents have in parallel started to consider broader dialogue, with each side coming with its own perspective on what it can achieve through peace talks.

Perspectives on Dialogue

Two years ago, neither JNIM nor Malian state officials and their foreign partners would publicly support the idea of dialogue. Authorities repeatedly said they “do not negotiate with terrorists”, while militants asserted that they do not “bargain about God”. Yet, in 2020, both the Malian government and JNIM’s leaders softened their stance. This shift may be due to the abovementioned stalemate and the unforeseen surge in communal violence, as well as the protagonists’ perception of negotiations as an opportunity to achieve their goals by means other than fighting. Resistance to dialogue persists, however: France publicly opposes engaging militant leaders, while many state officials and jihadists cling to maximalist expectations and remain wary of embracing peace talks.

A Course Change

In February 2020, then President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta said his government was willing to explore dialogue with Malian jihadist leaders, an announcement that many observers saw as a breakthrough.

Weeks earlier, Keïta’s high representative for central Mali, Dioncounda Traoré, asserted that he had sent emissaries to initiate talks with ag Ghaly and Koufa. The details of these talks never became public.

Engaging militants had been tried before. In 2017, Malian officials, backed by the prime minister (but not, it later emerged, President Keïta), launched an ambitious dialogue initiative known as the mission de bons offices.

Conducted by Mahmoud Dicko, an influential cleric who presided over the High Islamic Council of Mali at the time, the mission focused on communities that could facilitate talks with local militants, who would then help establish contact with their leaders. The goal was to advance peace through dialogue between a team of religious leaders and traditional notables, on one side, and JNIM affiliates, on the other. Despite a promising start, the mission was short-lived, mainly because it lacked Keïta’s support –he later said he had never approved it. Indeed, the former president was known as a staunch opponent of such talks.

Two interrelated phenomena likely caused his change of heart in February 2020. Violence had surged in the preceding year, with unprecedented mass killings of civilians and large-scale raids on military outposts that left hundreds of soldiers dead. Overwhelmed by the security crises, officials began to acknowledge the limits of the military response and consider talks with militants as an alternative. The Malian public, meanwhile, began to demand that the government reach out to jihadists. At first, calls for dialogue emanated from opinion leaders. In 2017 and 2019, respectively during the Conférence d’Entente Nationale and the Dialogue National Inclusif, participants recommended that the government organise talks with ag Ghaly and Koufa, the most prominent Malian insurgent leaders.

But as the security situation continued to deteriorate, the proposal gained increasing traction among the public. The civilian massacres of 2019 and 2020 were particularly frightening and triggered a series of protests.

A military coup ousted Keïta in August 2020, before dialogue could take shape. The interim authorities who replaced him initially upheld the decision to engage with jihadists. Early in the transition, then Prime Minister Moctar Ouane (September 2020-May 2021), a civilian, positioned himself as an outspoken advocate of talks, saying they were “in line with the will of the Malian people”.

Indeed, the transition’s roadmap described dialogue with militants as a core government policy. In his cabinet’s action plan, Ouane provided details of engagement, which revolved around three premises. First, the plan said, the government would engage in broad-based, grassroots dialogue via the mission de bons offices aiming to reconcile aggrieved citizens and the state. Secondly, and in parallel, military intelligence officials would reach out to the jihadist leadership to explore talks. Lastly, even as it pursued dialogue, the government would step up its military campaign and development efforts intended to undermine the insurgents.

In contrast, the junta’s leaders did not publicly comment on the issue.

But both Assimi Goïta, the junta’s top official, and Ismaël Wagué, in charge of the ministry of national reconciliation, supported dialogue between residents and jihadists to alleviate communal friction in central Mali. In October 2020, the transitional authorities concluded one of the largest prisoner exchanges in the Sahel’s history with JNIM. The government freed nearly 200 prisoners, including well-known JNIM militants, in exchange for the release of four JNIM-held hostages: Malian opposition leader Soumaïla Cissé, French citizen Sophie Pétronin and two Italians. Ahmada ag Bibi, a Kidal-based politician and long-term companion of ag Ghaly, together with Malian intelligence officials, led the negotiations on the government’s behalf. JNIM was represented by Sedane ag Hitta, ag Ghaly’s right-hand man in Kidal.

Ouane’s action plan faded from view in May 2021, however, as the junta removed the interim premier along with the interim president, Bah N’Daw, in a second coup following disagreements over a cabinet reshuffle.

” While public support for talks has clearly increased, many politicians, civil society representatives and religious leaders harbour deep reservations. “

Still, views on dialogue diverge. While public support for talks has clearly increased, many politicians, civil society representatives and religious leaders harbour deep reservations. Most doubt that JNIM’s leadership is willing to compromise. For instance, even Dicko, a pioneer of the pro-dialogue discourse in Mali, questions whether ag Ghaly and Koufa will ever accept a political settlement.

Though he supports direct engagement with JNIM’s leadership, Dicko cautions that the two may be too entrenched in jihad to lay down their weapons. But he does see promise in talks that could coax rank-and-file militants away from the insurgency and back to civilian life. Other officials fear that dialogue is equivalent to “opening the gates of power to JNIM”.

Many political leaders find jihadist demands, including the Islamisation of law and state institutions, particularly worrying. They see very little room for compromise on these matters, since the Malian constitution enshrines secularism, democracy and the nation-state as fundamental principles. Agreeing to skirt – or worse, in their view, to alter – these principles might be political suicidal for them, both in domestic opinion and with foreign partners. Some argue that the public’s call for dialogue is born of despair, as insecurity spreads and the authorities struggle to contain it, rather than willingness to consider jihadist demands, let alone support for them.

Still others perceive JNIM’s leaders as instruments of foreign jihadist networks, lacking autonomy.

Persistent French diplomatic pressure eventually convinced Mali’s transitional authorities to shy away, at least in public, from backing direct talks with JNIM’s leadership.

In private talks at first, and publicly later, France said it would withdraw its troops from Mali if the interim government engaged, strong-arming Malian officials into giving guarantees that such talks were off the table. In June 2021, shortly after the second coup, Paris suspended its cooperation with Bamako’s security forces partly over concerns the junta might start talking with jihadists.

Joint military operations have since resumed.

The transitional authorities have also sent equivocal signals. In May 2021, the junta brought in a new prime minister, Choguel Kokalla Maïga, who has acknowledged widespread public support for talks with jihadists and whose action plan mentions the mission de bons offices as a means of getting them started.

On 19 October, Mali’s religious affairs minister, Mamadou Koné, said he had instructed the High Islamic Council to lead the mission. Three days later, however, the government said no one had been officially mandated to start negotiations, while thanking those who had come forward to offer their services.

In short, vis-à-vis talks, the government has at best taken two steps forward and one step back.

B. JNIM’s View on Dialogue

In March 2020, in response to Malian officials’ call for dialogue, JNIM leaders published a statement saying they were ready to talk with the government.

In the following weeks, the insurgents pressed the authorities to cut ties with France so that direct negotiations could commence, accusing the government of dragging its feet. Their appetite for dialogue, however, was not a pledge to disarm and surrender. On the contrary, militants likely expected to gain the upper hand in eventual talks.

” JNIM’s leaders see dialogue primarily as a means of pushing foreign troops out of Mali. “

JNIM’s leaders see dialogue primarily as a means of pushing foreign troops out of Mali. The jihadist leadership explicitly conditioned talks on the withdrawal of French and international forces.

They perceive the international forces as an obstacle to their project of expanding their control. They particularly resent France because of its colonial history in the region and because its 2013 military intervention ended their short-lived rule in the north. Yet JNIM’s goal is not to defeat the French forces in combat; it is to deny France victory. JNIM hopes to drag France into a protracted war that will exhaust its army until Paris loses the will to fight.

Demanding the withdrawal of foreign troops is consistent with the pragmatic attitude that JNIM appears to have taken toward dialogue in Afghanistan. It welcomed the U.S.-Taliban negotiations that eventually led U.S. troops to leave the country in August. In a congratulatory letter, al-Qaeda General Command said the deal was a lesson for jihadists across the world, urging them “to follow the example of the Mujahideen of the Islamic Emirate”.

For JNIM, the U.S.-Taliban deal may even offer a model to emulate in reaching a settlement with Paris. In January 2021, JNIM pointed out that it has never staged an operation on French soil, a seeming reference to the Taliban’s pledge to stop other militants based in Afghanistan from staging attacks outside the country, which appears in the U.S.-Taliban agreement.

JNIM’s acceptance of talks seemed meant to woo rural dwellers, win popular support for its cause and bestow legitimacy upon its demands. It was framed as a courtesy to an exhausted public, which had been pleading with the government to consider dialogue. Indeed, JNIM’s statement addressed the Malian people rather than the government.

It also coincided with a wave of anti-French sentiment in the country. Throughout 2019 and into early 2020, opposition and civil society leaders organised a series of mass protests calling for the departure of Operation Barkhane troops and UN peacekeepers, whom they said had failed to stem insecurity. JNIM tried to capitalise on the public’s frustration by saying they shared the protesters’ demands, while castigating the government for siding with France.

There may be more at play in JNIM’s calculations about dialogue than mere opportunism. Both the military stalemate and genuine concerns about spiralling intercommunal violence may have influenced JNIM’s decision. JNIM has attempted to show empathy with ordinary Malians’ suffering, particularly among Fulani who are close to them.

Militants often accuse France and the Malian government of stoking communal violence as part of a divide-and-conquer strategy. To guard its own reputation in this regard, JNIM goes so far as to deny responsibility for the massacres in central Mali, despite its forces’ involvement in killing civilians, including in those massacres. In several statements, JNIM leaders have urged fighters to spare villagers, arguing that jihad prescribes the protection of civilians.

Whether the desire to appear compassionate could motivate JNIM to negotiate in good faith remains unclear, however.

The degree of consensus within JNIM about talks is also hard to assess. Of particular interest is the position of the Katiba al-Furqan, which tends to recruit foreign fighters and answers directly to AQIM. While former AQIM commander Droukdel, who was killed in a French drone strike in November 2020, was an outspoken advocate of dialogue between JNIM and the Malian government, his successor al-Annabi appears more sceptical.

More generally, dialogue is controversial in militant circles, generating heated discussions. In the wake of the U.S.-Taliban deal, jihadist ideologues around the world debated the righteousness of talking with governments.

JNIM katibas – including al-Furqan – have thus far refrained from taking a public position.

Koufa previously expressed interest in talking with religious leaders, including Dicko. At the same time, he deferred to ag Ghaly as having the last word, especially with regard to political negotiations. His deference attests to how firm ag Ghaly’s authority is. Yet even within the Katiba Macina, dialogue is a contentious issue. In November 2019, several Katiba Macina combatants defected to join ISGS, citing discontent with the Katiba’s willingness to enter talks with Dogon militia or the government among the reasons for their departure.

” JNIM lacks a political office that can translate its ideology into practical demands and make the group more amenable to negotiations. “

An additional handicap for JNIM is the lack of experienced political figures beyond ag Ghaly. Back in 2012, when the insurgency started in northern Mali, several high-profile politicians and intellectuals from Kidal – including Alghabass ag Intalla, Ahmada ag Bibi and Mohamed ag Aharib – made up Ansar Dine’s political wing.

They represented the jihadist group during negotiations in Burkina Faso and Algeria in the same year. But the team fell apart after its members died or broke away to form a new political movement (the Haut Conseil de l’Unité de l’Azawad) which signed the June 2015 Algiers peace accord. Those who have since emerged as leaders are either military or religious figures. JNIM lacks a political office that can translate its ideology into practical demands and make the group more amenable to negotiations and even were it to establish one, might struggle to find apt representatives.

Overall, JNIM’s willingness to take concrete steps toward dialogue or make concessions with its enemies as part of talks is an open question. There is no evidence that it would be as flexible in talks as it has been in applying Sharia. Additionally, JNIM has never clarified the institutional and political systems it might like to see established. Further, as noted above, even the jihadists’ motivations to engage in talks are unclear. JNIM leaders may envisage a political settlement, but they are just as likely to perceive military victory as the only possible endgame and talks as a means of getting rid of foreign forces so as to achieve that, as has ended up happening in Afghanistan. Uncertainty about what JNIM wants to talk about is a major obstacle to starting negotiations.

C. Mali’s Partners’ Stance

Paris has championed hardline opposition to dialogue for several reasons. In November 2020, President Emmanuel Macron said: “We do not talk with terrorists; we fight”.

More recently, Macron labelled ag Ghaly and Koufa “enemies” and designated JNIM as the main target of French and Sahelian counter-terrorism efforts. Paris is understandably reluctant to encourage talks with a group that has killed French soldiers. It is worried that dialogue will help legitimate JNIM’s demands and embolden jihadists to try imposing their version of Islam on Mali. As France can use its military presence in the Sahel as leverage to align the Sahelian governments’ positions with its own, its resistance to talks is a major obstacle. France may also be able to obstruct dialogue if it begins. In November 2020, as the idea of engagement gained momentum following the prisoner swap, a French airstrike killed Bah ag Moussa Diarra, a JNIM senior commander. Malian media interpreted the raid as an attempt to thwart any broader talks the exchange could have generated. A French diplomat in Bamako rejected this claim.

That said, France has on one occasion supported dialogue with insurgents who were prepared to defect and disarm. In 2013, France encouraged Ansar Dine members to create a new movement with which talks would be acceptable. Ansar Dine defectors then founded a Mouvement Islamique de l’Azawad, but soon rebranded it as the Haut Conseil de l’Unité de l’Azawad after French officials told them to drop any reference to Islam. The group signed the 2015 Algiers peace deal with the government though, like other signatories, it has never disarmed.

France is not alone in opposing dialogue with jihadist leaders in Mali. Some U.S. diplomats also reject this option. In an interview with Jeune Afrique, Ambassador Andrew Young, deputy to the commander for civil-military engagement at U.S. Africa Command, said: “There is no negotiation possible with those who carry out attacks against civilians, murder children and advocate for a worldview that is incompatible with the values of democracy and tolerance”.

He added, however, that he supports the idea of talks with locals who have been indoctrinated by jihadists.

Beyond their opposition to talks with jihadists, France and most of Mali’s partners also resisted attempts to include matters of religion in the negotiations that led to the 2015 accord. During preliminary talks in 2014, the Haut Conseil’s secretary general, Alghabass ag Intalla, suggested that discussions include the principle of laïcité (secularism) and the role of Islam in Mali.

The mediation team supervising the talks rejected his proposal, calling religion a red line. The peace agreement signed in 2015 barely mentioned religion, except for the qadis’ role in rendering justice in northern Mali.

” France’s closure of bases in JNIM strongholds in northern Mali seems likely to play into jihadists’ hands. “

That said, France is exasperated with Mali’s deteriorating security situation and deepening political crisis. In June 2021, Macron acknowledged that French military strategy was ill suited to the conflict’s contours, announcing that France would slash its troop deployment by about half and close three military bases in northern Mali as it draws the Barkhane mission to a close.

Instead, the Takuba task force will take the lead role in counter-terrorism operations, with special forces from France and other contributing European countries. Sahelian armies “that wish it” can still request training and support. As was to be expected, JNIM leaders hailed Barkhane’s end as a victory for jihad.

Indeed, though it is too early to foresee the consequences, France’s closure of bases in JNIM strongholds in northern Mali seems likely to play into jihadists’ hands.

France’s decision to reduce its military presence has soured relations with Mali’s transitional government. In September, Maïga described the partial withdrawal as “abandonment” in a speech to the UN General Assembly in New York. He alleged that France had not consulted Mali before taking the decision, leaving Bamako in search of alternative security partners. Maïga’s speech caused an outcry in Paris, with Macron labelling his comments “unacceptable” and dismissing his government as having no credibility. The junta is reportedly negotiating with the Wagner Group, a Russian private military contractor, for the deployment of at least 1,000 mercenaries. Some observers suggest that in contacting Wagner, Bamako is merely seeking to ramp up pressure on Paris to maintain its support, but the government’s exact motives are unclear.

France, alongside several countries that support the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali, is fiercely opposed to Wagner’s involvement. A complete breakdown of ties is therefore likely should Mali decide to hire a mercenary force.

Some external partners seem keener to talk. For instance, UN Secretary-General António Guterres has said: “There will be groups with which we can talk, and which will have an interest in this dialogue to become political actors in the future”. Guterres excluded groups affiliated with the Islamic State, however, arguing that “there are still those whose terrorist radicalism is such that there will be nothing to be done with them”.

Espousing similar views, former AU Commissioner for Peace and Security Smail Chergui has encouraged African states to explore dialogue with jihadists. But overt UN support for such talks is implausible given that the UN and all five permanent members of the Security Council have designated JNIM as an al-Qaeda-linked terrorist organisation. Still other foreign powers have refrained from taking a stance. Many diplomats, including from Germany and Canada, say that Sahelian states should decide for themselves about dialogue.

Enabling Dialogue with JNIM

The military stalemate and political quagmire that Mali finds itself in offers authorities an opportunity to review their approach to dialogue. Until now, the Malian government’s half-hearted acceptance of dialogue opened channels of communication with jihadists affiliated with JNIM in central Mali but offered little concrete beyond the prisoner exchange and ad hoc ceasefires. While dialogue comes with risks and will certainly spark controversy among Malian elites and foreign partners, it is an underused tool that could change conflict dynamics and potentially even lay the groundwork for long-term peace.

To be sure, talks would be a leap into the unknown that carries dangers for a government already weakened by internal power struggles.

Dialogue with jihadists is likely to further polarise Malian society if the government appears willing to accept compromises that restrict people’s freedoms, in particular those of women, or privilege Salafi strands of Islam to the detriment of others. As outlined above, secular elites, human right activists and Sufi Muslims could mobilise against talks. Secondly, it is unclear how dialogue would affect the implementation of the 2015 Algiers peace agreement and other planned reforms, such as revision of the constitution. Thirdly, it may impede the state’s ability to adhere to international commitments – in particular those concerning respect for human rights – that underpin Mali’s partnership with many foreign actors. Some external partners may decide to suspend their engagement with Mali as a result.

Last but not least, given the Malian state’s fragility, JNIM is likely to have the upper hand in eventual talks. Dialogue could also bestow legitimacy upon the militant coalition while conversely undermining the position of foreign actors who adamantly oppose its ideology and dismissed the possibility of allowing the group to encroach on Mali’s politics.

But the past eight years have shown that a military approach alone is not a viable solution. Furthermore, Mali would be ill advised to rely on French and other foreign nations to maintain a sizeable number of troops in the country indefinitely. Not only does these actors’ resolve seem uncertain, especially in light of Mali’s recent overtures to Wagner, but their withdrawal also could be as quick as France’s unilateral decision to overhaul Barkhane or, indeed, the U.S. pullout from Afghanistan. Should Malian authorities explore dialogue now, they will at least avoid having to rush into negotiations out of desperation or under public pressure, which would reduce their bargaining power.

Pursuing an all-out military victory may not work to JNIM’s advantage, either. As mentioned above, counter-terrorism forces have named ag Ghaly and Koufa as priority targets, pledging renewed efforts to kill them. JNIM has thus far survived the elimination of several mid-level commanders, but ag Ghaly’s removal would likely deal an enormous blow to JNIM, given that he has no heir apparent.

There is a long way to go before such dialogue can come about, however. Malian officials and the JNIM leadership can take four concrete steps to render talks a viable option. First, they need to bolster their commitment to peace talks and defuse resistance within their ranks. Secondly, they should appoint high-level negotiation teams to prepare an agenda. Thirdly, the Malian government should initiate a wider dialogue on the role of Islam in the state and society; it could do so under the auspices of planned national consultations. By establishing what Malians are ready to accept, the dialogue could yield potential compromises that could inform the two parties’ negotiating positions. Finally, the government and insurgents should decide who could serve as mediator. These steps would remove important obstacles to dialogue and send a clear signal that both sides are willing to pursue a settlement through non-military means.

A. Easing Resistance to Dialogue

The Malian government and JNIM’s leaders first need to bring those who resist dialogue on board. Malian authorities will need to persuade France, in particular, to allow high-level talks to take place. To this end, state officials will need to engage in shuttle diplomacy and lay out the potential gains of such talks and how they would protect foreign partners’ interests.

Foreign support for talks and close coordination between Mali and its partners will be critical for any settlement. While, again, the dynamics of any talks will very different from those in Afghanistan, the Taliban’s rapid seizure of that country illustrated how important it is that withdrawal of foreign forces is carefully sequenced with a peace deal between the government and insurgents. The state should not engage in dialogue without the support of its international allies. At the same time, the Malian authorities will need to reassure their foreign partners that they will condition any settlement with JNIM upon the latter’s commitment to – at a minimum – refrain from attacking foreign interests in Mali or using Malian bases to carry out attacks in other countries and, to the best of its ability, stop other militants from doing so. In this respect, Malian officials could hold JNIM leaders to their word: they have asserted that they attack only countries that have attacked them while remaining “at peace with those who behave peacefully with them”.

Ideally, JNIM would fully break ties with al-Qaeda itself as part of negotiations.

” French authorities should afford Malians leeway to explore new ways to address the conflict. “

Both Mali and France face difficult balancing acts. While asserting its desire for dialogue, Bamako needs to convince France to maintain its troops, which have so far contributed to preventing militants from seizing important towns. A precipitous withdrawal or drastic downsizing of French forces would most likely shift the balance of power in JNIM’s favour. For France, Paris risks losing influence over Sahelian states if it continues to reject talks. As violence persists, domestic pressure in favour of dialogue is likely to increase in Mali and authorities may decide, whether rightly or wrongly, to pursue it without France’s support. Instead of clinging to their opposition, French authorities should afford Malians leeway to explore new ways to address the conflict. Paris could also help in other ways, for instance by adjusting its military response if the Malian government and JNIM decide to engage.

French troops could suspend or temporarily limit military operations in JNIM-controlled areas while talks are taking place. Paris could also condition a drawdown on JNIM’s firm commitment to making concessions.

To be sure, with elections approaching in Mali (initially scheduled in February, but now postponed sine die) and France (April 2022), exploratory talks need to be suitably timed.

Mali’s interim authorities face a tight deadline for completing the transition, while the May 2021 coup, the country’s second in less than a year, has raised concerns about whether the junta truly intends to hand over power.

Similarly, foreign policy in the Sahel and beyond is likely to influence, even if marginally, French public opinion as the presidential election campaign kicks off. Macron, who will probably seek a second term, may stiffen his opposition to talks with jihadists who have French soldiers’ blood on their hands. Newly elected officials with a fresh mandate in either country might be in a better position to carefully weigh the importance of dialogue.

For their part, JNIM leaders will need to soften their stance on foreign troops in the region. Dialogue is unlikely in the near future if the jihadists continue to condition talks on these forces’ withdrawal. Instead, foreign involvement should be a topic for discussion during negotiations. Another hurdle is opposition among Malian government officials to JNIM’s link with al-Qaeda’s transnational network as well as the foreign militants in its ranks. While the Malian authorities strive to convince France to assume a secondary role, JNIM leaders should endeavour to reconsider the group’s ties with foreign affiliates, in particular AQIM, but also the Katiba al-Furqan’s foreign fighters. As part of negotiations, state officials might push for JNIM to cut ties with al-Qaeda during talks. There is precedent: Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham – formerly an al-Qaeda affiliate involved in the Syrian civil war – broke with the transnational network partly in an attempt to win international acceptance.

Appointing Negotiators

The Malian government and JNIM leadership could send a clear signal about their intentions by appointing credible negotiators. These teams should define negotiation strategies and priorities. Given the range of potential topics, mediation teams should include senior political leaders, Islamic scholars and other notables.

” Given the need to discuss the role of Islam in public life, mediation should include … influential Islamic scholars and community leaders. “

On the government side, this team should be composed of high-profile figures with experience in understanding jihadist perspectives. There is no dearth of capable negotiators who can represent the state. As described above, Malian governments previously appointed religious scholars, senior politicians, northern representatives and, more recently, intelligence officials to engage jihadists. Intelligence officials can be effective in brokering transactional deals and hiding potentially embarrassing or contentious talks from public view, but talks about core political, institutional and religious principles should be handled by experienced political and religious brokers. Given the need to discuss the role of Islam in public life, mediation should include – but not be limited to – influential Islamic scholars and community leaders.

For their part, JNIM may need to create a political office in another country, similar to the one the Taliban established for the Qatar talks, which played a crucial role in facilitating dialogue between the Afghan insurgents and the outside world. Options might be Mauritania or Algeria, though the current diplomatic standoff between Paris and Algiers would complicate a political office there.

Ideally, the JNIM negotiating team would comprise Malians and at least one top commander, whether it is ag Ghaly, Koufa or ag Hitta, the latter being the architect of the prisoner swap. Both ag Ghaly and Koufa are subject to international sanctions, including those imposed by the UN, the U.S. and France, while in France many accuse ag Hitta of ordering the murder of two French journalists. Should these men be part of the negotiations team, Mali’s foreign partners will have to suspend sanctions in order to allow them to travel to the country hosting dialogue. In the Taliban’s case, the UN did the same for some insurgent leaders.

C. A Wider Dialogue on Sharia and Secularism

So far, the two parties have maximalist expectations that contrast with their pragmatic attitude on the ground. The militants demand changes in line with their ideological discourse, aiming to impose their ultra-conservative version of Islam on the state, its institutions and the Malian public. Conversely, the Malian government upholds the principle of secularism. The gap between the two sides appears so enormous that many are doubtful compromise is possible. Yet the sides might be able to find common ground during talks, particularly on the role of the qadi.

Any talks would inevitably touch on the role of Islam in Malian society, but the implementation of Sharia, in particular, is a question that concerns the Malian people first and foremost and one that should not be left to the protagonists to debate among themselves. The Malian government should therefore facilitate a public debate on the role of Islam in determining the state’s institutional and political principles, the provision of justice and public moral codes.

Religion is part of daily life in Mali, and the insurgency has only intensified the debate on the role of Islam in society and politics.

Rural dwellers trying to settle family issues or land disputes have long preferred traditional or religious jurisprudence over modern courts. Some surveys suggest that a significant proportion of Malians would like religion to be more prominent in public life. According to an Afrobarometer survey in 2018, for instance, 55 per cent of respondents said Islam should become Mali’s official religion, while nearly half (46 per cent) favoured the implementation of Sharia, without specifying what provisions should be applied.

A public debate on the role of Islam would be a complicated and sensitive endeavour, but one that could help draw the contours of possible compromises and trade-offs between the government and JNIM’s leadership. The two sides could then use the outcome to think through their own positions before entering into negotiations.

The timing is favourable. The transitional government has pledged to hold national consultations on key political and institutional reforms, including a constitutional review. Preparations for these Assises Nationales de la Refondation are already under way. The government could broaden the Assises to include discussions on the role of Islam in local, regional and national affairs. Furthermore, such discussions could elaborate on provisions in the 2015 Algiers peace agreement, particularly the qadis’ role.

The Malian government and the jihadists appear to agree on the qadis’ relevance, even as views diverge on the scope of their jurisdiction. The justice ministry has been developing a draft law to enhance the function of qadi and the role of traditional authorities throughout Mali since 2019, following the government’s assent to do so in the Algiers accord.

Jihadists, meanwhile, allow residents of areas they control to choose their own judges. Most qadis in northern and central Mali draw upon the key texts of Maliki jurisprudence in making their rulings. Under the jihadists, qadis cover all judicial matters, while the government supports a dual system in which Islamic and modern courts complement each other, a common practice in the central Sahel. The government could condition the formalisation of qadis’ role on the jihadists’ acceptance of secular courts.

The Malian government and jihadists could also draw lessons from other countries in the region, such as Mauritania and Nigeria, to reconcile religious beliefs with the state’s republican character. For instance, the central state could allow districts to adopt laws in keeping with the prevalent local belief system, all the while respecting minority faiths, for example by referring their cases to customary jurisdictions or government courts. Rural communities would thus have a say in the way they are governed, which might bolster the state’s legitimacy if people see the measure as responding to local needs. Such out-of-the-box thinking might create opportunities for dialogue.

When engaging in talks on these issues, Malian officials will undoubtedly receive criticism from outside allies and domestic secular elites. The idea of Sharia generally elicits consternation in Western capitals. Malian officials may see a state-backed religious debate, and eventually a deal with the jihadists, as undermining the state’s secular character. A wider dialogue on the topic is thus all the more important. That said, formalising Sharia courts that already pass judgment and resolve disputes across parts of the country is unlikely to significantly alter existing practices.

D. Finding a Mediator

Dialogue between the Malian government and JNIM is likely to hit obstacles that might be insurmountable absent the services of an experienced, mutually acceptable mediator.

Several countries could assume the role. Algeria has some leverage over JNIM leaders because it could restrict their movements by tightening the border or deny their families safe haven. It negotiated an accord with a homegrown jihadist movement. Moreover, Algiers has already mediated between the Malian government and rebel groups, albeit with mixed results. Many observers, including Crisis Group, criticised the Algiers-mediated 2015 deal because international mediators imposed their own agenda during the talks, limiting time for exchanges between belligerents, and implementation has lagged.

Qatar might be an option, given its track record as facilitator of U.S.-Taliban talks. Doha may be able to earn the Malian government’s and JNIM’s confidence, though its involvement would risk alienating Qatar’s main Gulf rival, the United Arab Emirates.

Finally, Mauritania has experience in initiating religious debate between jihadists and local Islamic scholars, though lacks technical expertise in mediation. Other alternatives include Norway or Switzerland, which have significant relevant experience.

The mediator will need technical assistance to sketch proposals for compromise, including on constitutional reforms, justice reform, disarmament and the structure of a new army. Independent mediation NGOs could provide such advice. Organisations like the Switzerland-based Center for Humanitarian Dialogue and Paris-based Promediation, for instance, have engaged both state officials and jihadists either formally or informally for years now and have the skills and knowledge to help.

VI. Conclusion

The time is ripe for the Malian government and JNIM to shift gears and commit to high-level talks. Both parties appear to perceive dialogue as an opportunity. France, whose counter-terrorism efforts in the region have contributed to maintaining the bloody status quo, has started to show signs of fatigue with the deteriorating security situation and Mali’s deepening political instability. Yet resistance to talks remains strong both in Mali and among its external partners. The protagonists are likewise hesitant to determine what they want to talk about, how they would like to talk and, more importantly, what compromises they are willing to make to reach a political settlement. As military victory remains elusive for both sides, and the death toll continues to climb, the Malian government and the militants should take concrete steps to enable dialogue by preparing the ground, appointing negotiating teams and deciding on a mediator. Dialogue will not resolve all the problems raised by the jihadist insurgency in Mali, nor should it mean the immediate end of military operations. But it has the potential to at the very least improve prospects for an eventual settlement, given that a military strategy alone is increasingly unlikely to end the violent impasse that the region finds itself in.