Islamist armed groups in Mali have killed hundreds of people and forced tens of thousands to flee their villages during apparently systematic attacks since March 2022, Human Rights Watch said. Malian security forces and United Nations peacekeepers should bolster their presence in the affected regions, ramp up protection patrols, and help authorities provide justice for victims and their families.

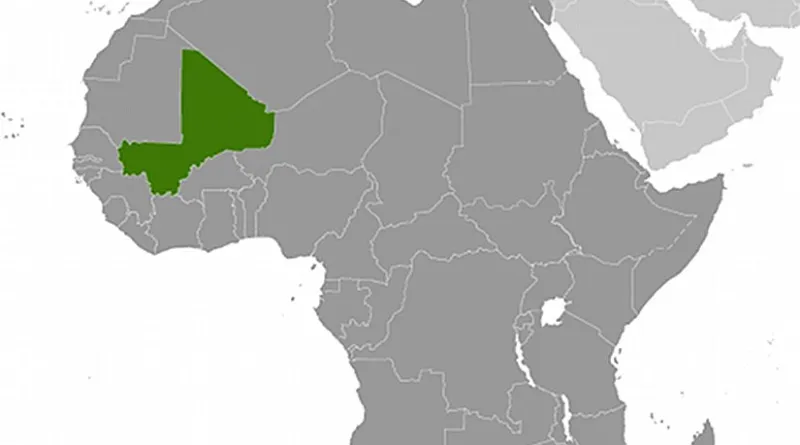

Since early in the year, Islamist armed groups aligned with the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) have attacked dozens of villages and massacred scores of civilians in Mali’s vast northeast regions of Ménaka and Gao, which border Niger. These attacks have largely targeted ethnic Dawsahak, a Tuareg ethnic group.

“Islamist armed groups in northeast Mali have carried out terrifying and seemingly coordinated attacks on villages, massacring civilians, looting homes, and destroying property,” said Jehanne Henry, senior Africa adviser at Human Rights Watch. “The Malian government needs to do more to protect villagers at particular risk of attack and provide them greater assistance.”

Between May and August, Human Rights Watch interviewed 30 witnesses to attacks between March and June on 15 villages in Ménaka and Gao regions. The witnesses described a pattern of heavily armed men on motorcycles and in other vehicles surrounding their village, shooting indiscriminately, summarily executing men and other villagers, and looting and destroying property. Often other villages in the region were attacked around the same day, suggesting a plan or directive. Tens of thousands of people who lost their livestock, livelihoods, and valuables have fled for elsewhere in Mali or to neighboring Niger.

A number of armed groups are active in the region and implicated in grave abuses. Security analysts believe the Islamic State in Greater Sahara now largely controls three of the four administrative cercles, or circles, of the Ménaka region through various Islamist armed groups. In addition, former rebel Tuareg groups, aligned with the Malian government since a 2015 peace deal are present, notably a Dawsahak faction of the Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (Mouvement pour le salut de l’Azawad, MSA-D) and the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defense Group and Allies (Groupe d’autodéfense touareg Imghad et alliés, GATIA).

There were almost weekly media reports of killings, destruction of villages, and mass displacement of civilians in Ménaka and Gao earlier this year. In May, the media reported attacks on several villages in Ménaka. A witness told Human Rights Watch that on May 22, heavily armed men on about 100 motorcycles invaded the village of Inékar in Ménaka and started shooting at the men, killing nine of his male family members. In June, the media reported an attack at Izingaz, in Tidermène circle, in which Tuareg groups alleged that 22 civilians were killed. In September, media reported that Islamist armed groups carried out a large-scale attack on Talataye commune in Gao, killing at least 42 civilians.

Community leaders have stated that nearly 1,000 civilians have been killed in the region since March. A local investigation committee member told Human Rights Watch that at least 492 were killed between March and June in Gao region alone, but believes the number is much higher since the committee did not investigate all attacked locations.

The current wave of armed Islamist group attacks followed a clash between the Islamic State group and MSA-D in early March. The Islamic State then apparently began to target Dawsahak villages, issuing a fatwa – a religious order or decree – against villagers they accused of allegiance to former rebel groups and a rival armed Islamist group, villagers said. The fighting between the armed groups led to attacks on towns and villages and their inhabitants in violation of the laws of war.

“They burned houses, took our animals and grain, and what they could not take they set on fire,” said a village leader who witnessed attacks on the town of Tamalate on March 8. A teacher who witnessed an attack on Intagoiyat village in March said, “They shot at everything. They just kill, they do not try to interrogate, they do not talk except ‘God is great’ and it’s over.”

The surge in violence coincides with France’s withdrawal on August 15 of its remaining troops deployed as part of a regional counterterrorism operation to Niger and other locations. It also reflects longstanding tensions among the region’s pastoralist communities, semi-nomadic herders dependent on dwindling water and pastures. While the vast majority of recent killings have been carried out by Islamist armed groups against the Dawsahak community, Human Rights Watch has also received reports of retaliatory attacks by pro-government armed groups against presumed Islamic State supporters.

Both the Malian army and the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), have forces in Gao and Ménaka. However, these troops do not patrol far from the towns and – particularly in Ménaka – have little or no capacity to protect civilians, including displaced populations, in remote areas. The UN mission should continue to ramp up its patrolling, deterrence flights, and interactions with the affected communities, Human Rights Watch said.

Islamist armed groups have also attacked civilians in other parts of Mali this year. Human Rights Watch investigated the June 18 attack on villages in Bankass circle in Mopti region, allegedly by the Katiba Macina, an armed group aligned with the Al-Qaeda coalition, that the government reported killed 132 villagers.

Human Rights Watch has for several years also documented serious abuses by the Malian security forces and forces widely believed to be with the Russia-linked Wagner Group, a private Russian military security contractor, during military operations.

“Malian authorities should work closely with the UN to provide better security for the population in the northeast and other conflict-affected areas of the country,” Henry said. “The UN and Malian authorities should improve security arrangements in threatened areas, engage more with local communities, and impartially investigate all reports of serious abuses.”