The rise of farmer-herder violence in Africa is more pernicious than fatality figures alone since it is often amplified by the emotionally potent issues of ethnicity, religion, culture, and land.

Highlights

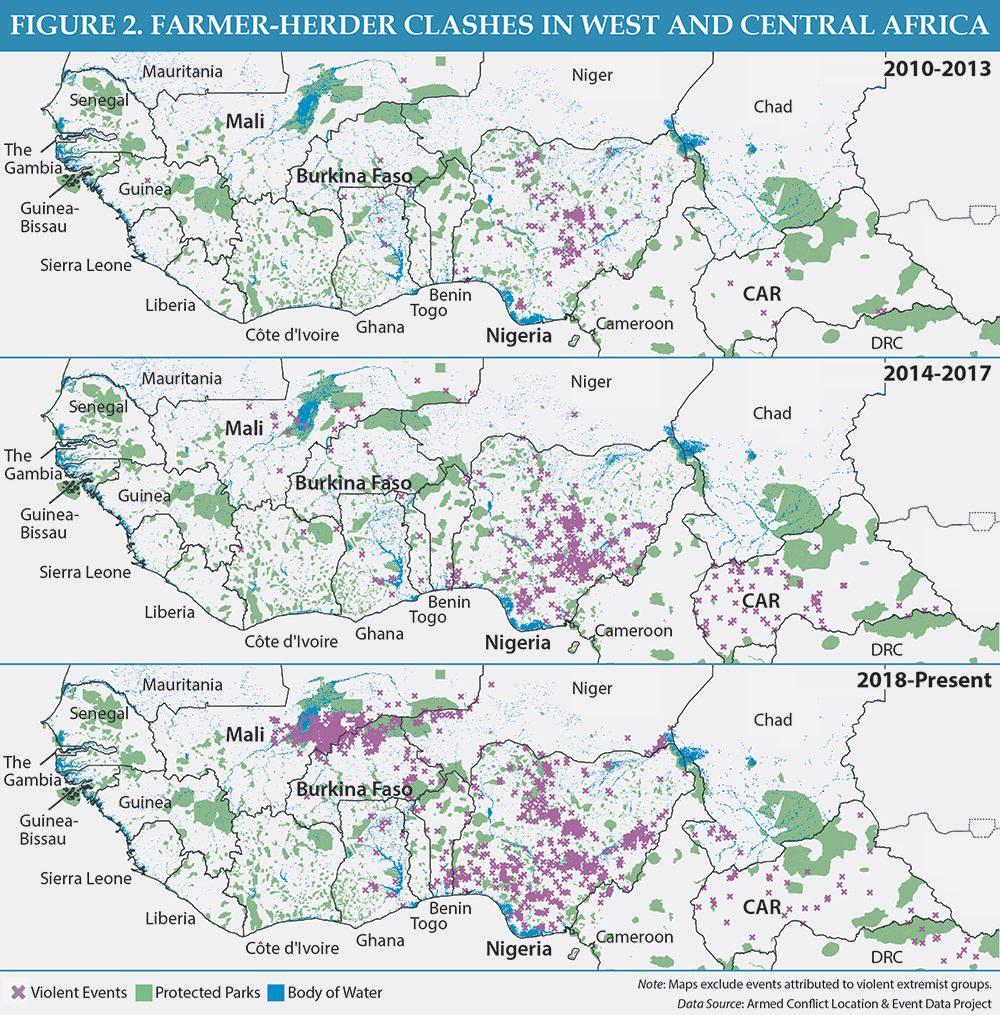

Farmer-herder violence in West and Central Africa has increased over the past 10 years with geographic concentrations in Nigeria, central Mali, and northern Burkina Faso.

Population pressure, changes in land use and resource access, growing social inequalities, and declining trust between communities have rendered traditional dispute resolution processes less effective in some areas, contributing to the escalation of conflict.

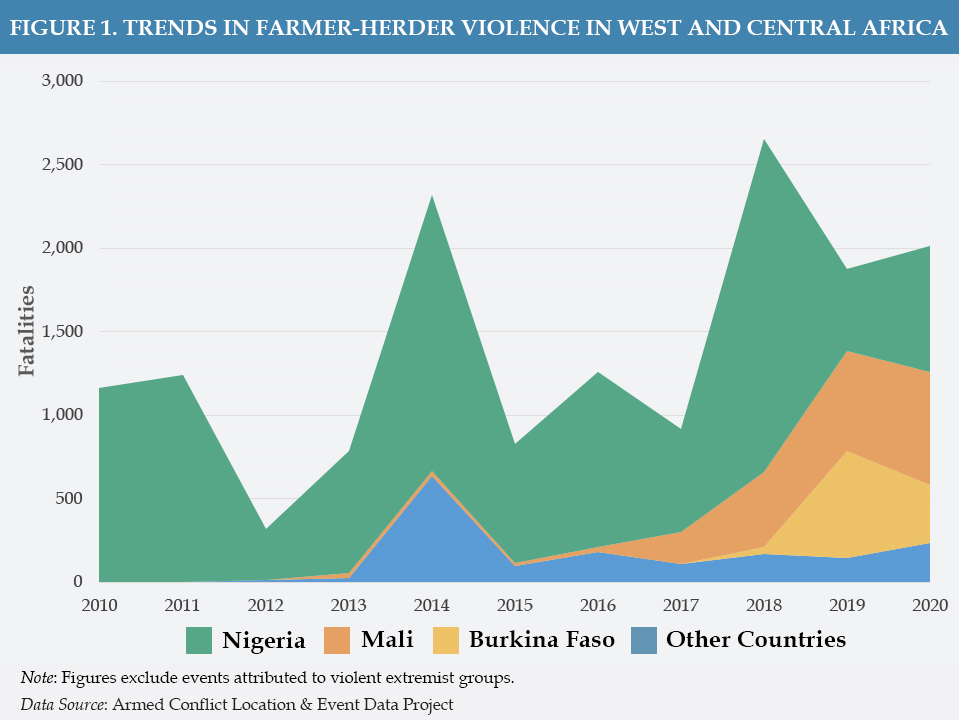

Militant Islamist groups in central Mali, northern Burkina Faso, and parts of Nigeria have exploited intercommunal tensions to foster recruitment. This has had the effect of conflating farmer-herder conflict with violent extremism, significantly complicating the security landscape.Violence involving pastoralist herders in West and Central Africa—as perpetrators and victims—has been surging in recent years. Since 2010, there have been over 15,000 deaths linked to farmer-herder violence. Half of those have occurred since 2018 (see Figure 1).

The rise of farmer-herder conflict in Africa is more pernicious than fatality figures alone, however, since it is often amplified by the emotionally potent issues of ethnicity, religion, culture, and land. Militant Islamist groups in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso have instrumentalized such divisions to inflame grievances, thereby driving recruitment. Similarly, rebel groups in the Central African Republic (CAR) have positioned themselves as defenders of pastoralist interests.

Ironically, most livestock herders have no association with extremist groups and are often victims of their actions. Nonetheless, once the genie of intercommunal conflict is unleashed, passions take over. Attacks become deadlier, expulsions more frequent, and reprisals extend to communities not immediately linked to the initial flashpoint. The stakes quickly shift from questions over resource access or local politics to deep-seated notions of identity. Entire communities are labeled bandits, insurgents, or terrorists.

Although farmers and pastoralists have held competitive relations for centuries, the current climate of violence is unprecedented in modern times. The relationship between manageable farmer-herder disputes and spirals of intercommunal violence is complex. Nonetheless, positive lessons exist even where violence has been most concentrated.

Drivers and Triggers of Farmer-Herder Violence

The surge in farmer-herder violence in Africa has been concentrated in Nigeria, along the central Mali and northern Burkina Faso corridor, and parts of CAR (see Figure 2). The fact that there are geographic hotspots underscores the importance of understanding the local and regional factors that have contributed to violent outcomes. It also highlights that most farmer-herder disputes are resolved amicably. Following is a review of some of these conflict drivers.

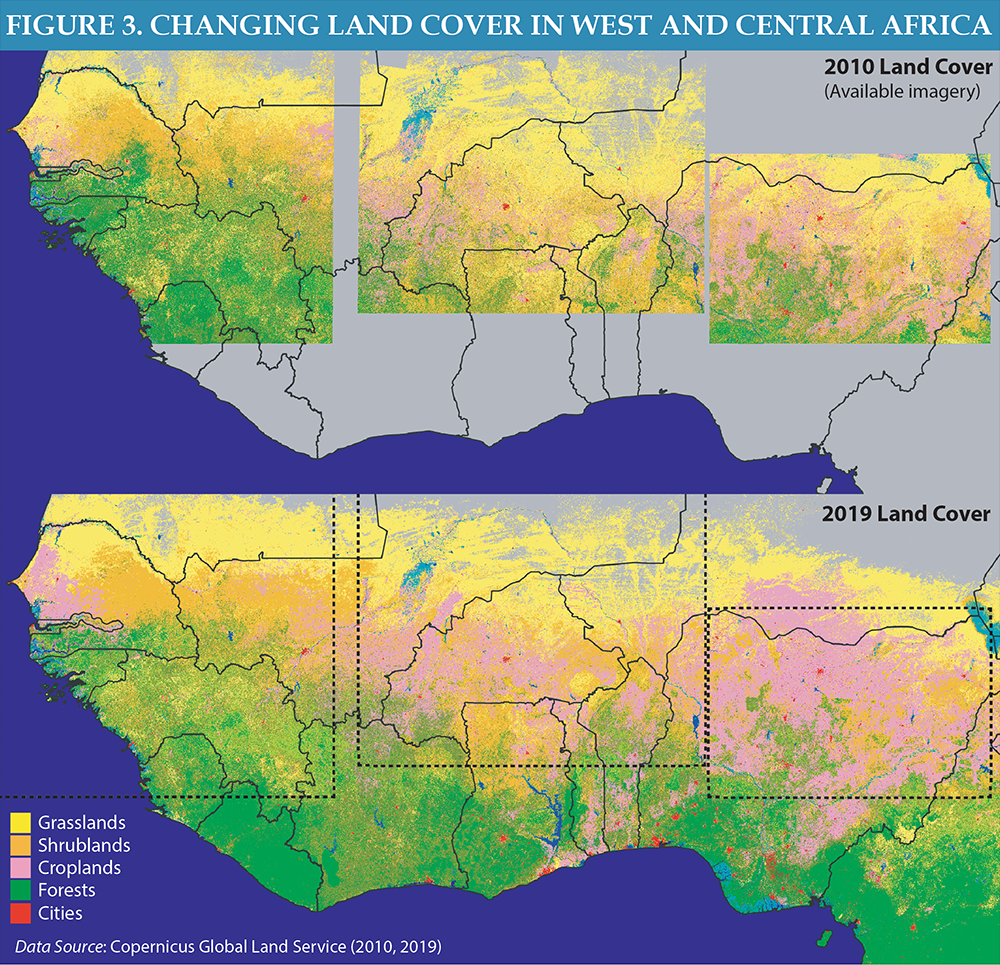

Growing land pressure. The most common trigger of farmer-herder conflict is crop damage caused by passing livestock. Although well-established local conventions dictate how such conflicts should be resolved, this process can break down. As the region’s rural population has grown dramatically, many herders have seen their grazing lands put into cultivation making their livelihoods more challenging (see Figure 3). The rural population in the Sudano-Sahelian zone of West and Central Africa has grown by more than 40 percent over the past 20 years, reaching more than 281 million people. Over the past four decades, cropland has doubled in area reaching nearly 25 percent of the total land surface, a trend that scientists project to accelerate alongside population growth.

Pastoral land scarcity pushes herders into protected areas, such as national parks and classified forests, and increases their dependence on nominally illicit practices such as tree branch lopping. Security and forestry agents responsible for enforcing these regulations are perceived as disproportionately targeting pastoralists in exacting fines and even committing violent abuses.1 Likewise, counterinsurgency campaigns in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria have worsened intercommunal relationships as security forces have at times acted against pastoralist communities seen to be supportive of violent extremist groups.

Dispossession. The encroachment of cultivated land into grazing areas deepens pastoralists’ grievance that their rights to resources—be it land, water, wood, or forage—are weaker than those of farmers and consequently have been ignored. Pastoralists typically only need seasonal access to resources, so their land rights are often treated as secondary to those of farmers. Similarly, land use decisions are often made when pastoralists are not present, effectively excluding them from the process. Even where laws aim to protect pastoral resource rights, they tend to go unheeded at the local level. For example, Benin has a strict law prohibiting cultivation within livestock corridors, but the laws are frequently disregarded because the corridors pass through traditional farming lands.

In some contexts, the lack of access to land has led young people to lose faith in their community elders who appear unable to protect their resource interests or are involved in land deals themselves. In Nigeria, grazing reserves and other lands under pastoral community control have been the target of elite land acquisition.2 Rural land deals generate significant exchanges of wealth and serve as rewards within patronage networks as national and state actors seek political support. The consequent intracommunity tensions can contribute to armed group recruitment as youth seek emancipation and an autonomous livelihood. Paradoxically, the presence of armed groups further reduces the availability of pastoral land as herders are expelled or prohibited from key areas like protected forests, which armed groups occupy.

Theft. Livestock is the most valuable resource across many rural communities and is a common target of theft. Increased frequency and magnitude of livestock theft is both a cause and effect of violent conflict. Armed groups use stolen cattle to fund their activities. The risk of theft causes herders to arm themselves to protect their animals. The increased demand for arms enriches criminal syndicates involved in arms trafficking. All these factors raise the risk of violent altercation. Meanwhile, aggrieved groups may perceive stealing livestock from communities with which they have been in conflict as a form of justice. This has led to a rapid expansion in the number of community-based armed groups to ostensibly guard against livestock theft, though such groups can also be engaged in reprisal violence. In many Nigerian states and parts of Central Africa, “war economies” have emerged around livestock trade networks and migration routes.3

“Distrust in the mediation process inhibits resolving routine disagreements amicably and informally.”Social inequalities. Recent shifts in livestock ownership in some locations from rural pastoralist communities to wealthy urban dwellers have generated perceptions that herders are representing elite interests. This has contributed to the breakdown of traditional systems of mutual dependence such as the sharing of crop residue. Conversely, this reinforces other conflict triggers such as the likelihood that a farmer will demand exorbitant fees of a herder for any damage to his crop. Similarly, a herder who has the backing of political elites may refuse to participate in dispute resolution with local farmers on the assumption that the owners of the herds hold sufficient political sway to avert accountability.4

Perceptions of social inequality also affect relationships within communities where local elites, typically clan elders or household heads, possess substantial economic and social power over their subordinates. In central Mali, this hierarchical community structure is codified within a neofeudal caste system and has allegedly contributed to grievances among youth and lower castes, which militant Islamist groups exploit to foster recruitment.5 Pastoralist-allied armed groups in CAR gained influence by protecting herders during that country’s internal conflicts, which subsequently led to a power struggle between those groups and traditional community authorities.6

Conflicts of interest and mistrust. Trusted dispute resolution institutions, including informal negotiations, serve as a linchpin for mitigating farmer-herder violence. If these adjudicating institutions are perceived to be subject to inducements, however, trust in the entire process is eroded. Distrust in the mediation process, moreover, inhibits resolving routine disagreements amicably and informally.

Once mistrust, rumor, and suspicion taint perceptions of the dispute settlement process, aggrieved parties and their allies are often quick to assume that corruption played a role. Conversely, if either party to a dispute rejects the involvement of authorities, confrontations may escalate into intercommunal standoffs that are quick to turn violent. These standoffs have historically involved traditional hunters’ associations such as the Dozo in Mali and the Koglweogo in Burkina Faso. These types of associations often serve as community militia because they have access to artisanal firearms and bush tracking skills. As pastoralist-affiliated militia have emerged, conflicts between the two groups have become more organized, protracted, and deadly contributing to self-perpetuating cycles of violence.

Farmer-Herder Conflicts in Nigeria

“Policies that effectively reduce the grazing land available to seminomadic pastoralists may also inadvertently fuel cycles of violence.”Nigeria has experienced the highest number of farmer-herder fatalities in West or Central Africa over the past decade. This trend has been largely upward, with 2,000 deaths recorded in 2018. Violent events between pastoralist and farming communities in Nigeria have been concentrated in the northwestern, Middle Belt, and recently southern states.

In response to the growing violence, several state governments in Nigeria have adopted anti-open grazing laws that require livestock to be brought to market by rail car or vehicle, rather than on foot, to reduce potential conflicts with farmers. Initially enacted in 2016 in four Middle Belt states—Ekiti, Edo, Benue, and Taraba—the laws are seen as outlawing nomadism, representing a threat to the lifestyle of some pastoralists. In Benue and Taraba States, the number of conflict events and fatalities have dropped substantially following the enactment of these laws, though it is unclear to what extent this can be attributed to their enforcement.

Similar strategies have gained momentum in other parts of Nigeria. Following the spread of farmer-herder clashes to the south, the governors of 17 southern states issued a joint resolution in May 2021 to ban open grazing in their territories.

Such laws and tactics are embedded within a hostile political discourse about Fulani pastoralists that echoes across West and Central Africa.7 This, in turn, makes long-term conflict de-escalation in Nigeria more difficult. For example, the Nigerian government and many other political actors strongly support the implementation of the 2019 National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP), which aims to improve security and reduce farmer-herder conflict by settling herders into ranches. Because the law favors local indigenous populations, it often supports farmers who wish to raise cattle. Pastoralists are often excluded from ranch development, however, as they commonly originate from other states or neighboring countries. This results in a framework that offers little help to seminomadic pastoralists and instead creates further barriers to land use and access. It does not address, therefore, the underlying drivers of polarization between farmer and herder communities.

Ranching is viewed suspiciously by many seminomadic pastoralists as it requires dramatic changes in lifestyle. That the initiative is strongly supported by anti-Fulani media voices makes its implementation even more polarizing. If the NLTP were to be more inclusive of pastoralists’ interests, it could potentially mitigate some pastoralism-related insecurity. However, flaws in implementation will likely undercut its effectiveness. For example, Benue State’s Open Grazing Prohibition and Ranches Establishment Law requires individuals who do not qualify as indigenes, which comprises many pastoralists, to follow a multistep permitting process that includes authorization from landowners. As a result, the law is unlikely to facilitate livelihood transitions or reduce the need for pastoral mobility. It is likely, however, to further exacerbate intercommunal resentments.

Policies that effectively reduce the grazing land available to seminomadic pastoralists may also inadvertently fuel cycles of militant violence. In search of land, herders are increasingly forced into forest reserves, which also serve as hideouts for criminal gangs and extremist groups. This exposes herders to cattle theft and other forms of insecurity to which many pastoralists have responded by arming themselves for protection.8 For local residents, this makes pastoralists increasingly indistinguishable from extremist groups. It also contributes to increased intercommunal tensions. In Adamawa State’s Madagali Local Government Area (LGA), which overlaps with parts of the Sambisa Forest, the presence of Boko Haram cells has forced pastoralists out of the forest leading to more crop damage and worse relations with local farmers.

Best Practices: Kabara Committees in Nigeria

Nigeria’s Adamawa State has been wracked by violent farmer-herder conflict since the early 2000s. However, in certain areas such as the Shuwa community, Kabara dispute resolution committees have stemmed the violence from farmer-herder disputes.9 Kabara, which means “common ground” in the Marghi language, functions as a grassroots mediation forum for all types of infractions and crimes including farmer-herder disputes. Comprised of community stakeholders from traditional and religious leaders, local authorities, and youth and women’s associations, the committees mediate disputes without recourse to excessively punitive measures, reducing the chance of conflict. Despite growing insecurity in the area around the Shuwa community, the inclusivity of its Kabara committees has helped avoid the farmer-herder violence that affects many of its neighbors by providing accountability and impartiality, which increase buy-in and participation from the parties to the dispute.

The Demsa LGA in Adamawa State has also contained violence due to a well-functioning grassroots forum that benefits from historically good relations between Fulani herders and M’bula farmers. An adequate level of intercommunal trust and the stature of key local political actors means that members of both groups treat the mediation forum as a legitimate way to resolve disputes. Even in places where trust has eroded over time, confidence-building measures such as peacebuilding dialogue between communities and mediation trainings for community leaders may help to restore trust and foster accountability in similar fora.

Municipal and district authorities can also play key roles in managing conflict and preventing violence. Adamawa State’s Girei LGA has experienced far fewer violent altercations than its neighbors due the effectiveness of its district head in conflict resolution fora. In this case, the individual also serves as the Ubandoma, a traditional office of the Yola Emirate administration, which considerably increases his local legitimacy.

Farmer-Herder Conflicts in Mali

In Mali, the cycles of farmer-herder violence and reprisal have become increasingly lethal since 2015, resulting in nearly 700 fatalities in 2020.

Most farmer-herder violence in central Mali is concentrated in the part of Mopti Region bordering northern Burkina Faso. Increasing population density is contributing to land tenure disputes. Efforts to negate or redefine longstanding autochthon-migrant relationships has been a volatile factor in certain localities.

“Local settlements that favor Fulani pastoralists will likely generate fresh land-related grievances.”The most immediate trigger to the surge in farmer-herder violence in this region, however, are militant Islamist groups. The Macina Liberation Front (FLM) led by Fulani cleric, Amadou Koufa, has strategically exploited intercommunal differences, playing up pastoralist grievances as a means to drive recruitment. As a result, Fulani now comprise the majority of militant Islamist group forces in the region. FLM achieved some local support through populist measures, such as banning grazing fees and by echoing the grievances of young herders against the established land tenure system in central Mali. Despite this, FLM does not appear to have broad-based support among the Fulani or pastoralists in general.10 In addition to recruiting through Koranic schools, the organization allegedly relies on coercion and intimidation to recruit new members (a practice also reported for armed groups in Nigeria), suggesting limited popular appeal. Nonetheless, the conflation of the Fulani and FLM identities fuels the perception that all Fulani are terrorists and earns the Fulani blame for militant Islamist group attacks in the region.

Tenuous truces between traditional or religious leaders, community-based armed militias, and militant Islamist groups in some localities have reduced violence between farmers and herders by including provisions on crop damage, land appropriation, and cattle theft. This was the case in central Mali’s Ténenkou District, one of FLM’s first target areas. The Ténenkou pact, which has the implicit support of both Malian security forces and FLM elements, keeps conflict mediation in the hands of local chiefs and imams and is enforced by the brutal justice meted out by FLM.11 In doing so, the agreement has also influenced the distribution of local political power. Notably, it excludes local political actors and peacebuilding civil society organizations, which are perceived as too close to the Malian state and its counterterrorism partners.

The long-term viability of such pacts is questionable for several reasons. While livestock theft in Ténenkou has diminished for Fulani pastoralists, this has not been the case for Bambara farmers, who also own significant numbers of cattle. Left unaddressed, these local settlements that favor Fulani pastoralists will likely generate fresh land-related grievances that eventually lead to a return of violence. The first farmer-herder truce, for instance, broke down when militant Islamist group violence persisted.12 The militant Islamist group tactic of targeting government services also impedes the provision of sustainable security. Likewise, since armed groups aggravate rather than address tensions around resource access, the risk of resurgent farmer-herder conflict remains high.

This tenuous equilibrium describes parts of central Mali where local authorities in some jurisdictions have not collected taxes since the Malian crisis began in 2012. Northern CAR exhibits similar dynamics where pastoralists engage in clientelistic relationships with armed groups who derive revenue from the pastoralists in exchange for privileged land access. If such coercive and extortionary arrangements emerge and persist in Mali, it is difficult to imagine that they will be able to address the long-term structural pressures such as resource competition that contribute to violence involving pastoralists.

Best Practices: RECOPA and Local Governance

The most effective way to prevent violent farmer-herder conflicts is to address their root causes, including pastoral herd mobility and resource access. Successful initiatives highlight the importance of multistakeholder approaches that involve customary authorities, elected officials, and civil society organizations that provide technical expertise and act as facilitators.

In western Mali, where pastoralists often come into conflict with local farmers, the mayor of Sebekoro facilitated and helped codify an agreement that farmers and herders established on their own. The agreement is partially based on national law, including the Pastoral Charter, and traditional arrangements through which settled herders facilitate the passage of livestock and mediate any incidents of crop damage before serious disputes arise. The agreement took the form of widely used local conventions that when coupled with the mayor’s careful involvement and the trust placed in him, contributed substantially to reduced crop damage in the area.

In eastern Burkina Faso, the Pastoral Communication Network (Réseau de communication sur le pastoralisme, RECOPA) has spearheaded an effort involving farmers and herders, communities, and the municipal government to overcome difficult land tenure obstacles and secure pastoral routes and grazing areas. RECOPA maintains basic land management infrastructure in the form of maps that are accessible to resource users and physical markers for land use boundaries. Funding initiatives based on collecting small amounts from market receipts help sustain its activities and generate communal ownership of the organization.

The Role of Security Forces

Security forces have an essential yet poorly understood role to play in mitigating farmer-herder conflict and breaking its link with regional insecurity. In countries where security forces have historically enjoyed higher confidence of local populations, such as Benin, they are typically called on to play a role in interrupting violence and preventing escalation. During the time Mali had a democratically elected government, Malian security forces were able to build on that legitimacy to defuse violent intercommunal standoffs that had the imminent potential to spiral out of control. This was especially apparent in Yanfolila District, Sikasso Region, where local security forces successfully calmed violent farmer-herder disputes by collaborating closely with community leaders. Even in Nigeria, where public confidence in security forces is among the lowest in the region, reports show that when they respond quickly and are equipped to de-escalate situations involving violence, state security actors can minimize the number of fatalities in an attack.

It is increasingly important for security actors to distinguish between local farmer-herder confrontations and militant Islamist group attacks and to reinforce mechanisms that reduce the risk of escalating violence while protecting communities. For example, disputes over individual incidents or rights to parcels of land can and do turn violent. Local authorities and security forces must address these incidents quickly and equitably to prevent them from stoking intercommunal tensions that may create the conditions for violent extremist group recruitment. In the meantime, community stakeholders should use land disputes as opportunities to reevaluate existing resource access agreements and find equitable solutions. Security forces can serve a critical role of deterring violence, providing space for these dialogues to run their course.

Recommendations

The surge in farmer-herder violence merits high priority given the potential for what are often land disputes to rapidly escalate into broader intercommunal conflict supercharged by emotive issues of identity—ethnicity, religion, and culture. Farmer-herder tensions will diminish when pastoralists feel included in decision making, especially concerning land resources, and when they feel their mobility is secure and presence respected. Farmers must feel confident their livelihoods will not be undermined by changes in laws regulating access to land and its use and that their own settlements and fields are secure. Security forces can and need to reinforce rather than destabilize these preconditions for violence reduction. Accomplishing these objectives will require that governments, civil society actors, and international partners prioritize the following.

“Security forces need to apply a discriminating approach in counterinsurgency efforts that protects exposed communities and vulnerable populations.”Differentiate between local grievances and armed extremist groups in high-risk areas. Communities that border protected forests and vulnerable populations such as young livestock herders are particularly at risk of violent exploitation by armed groups and becoming members of them either through recruitment or coercion. Herders who are far from home face additional risks because they may lack trusted contacts or even the ability to communicate with local people in areas where they seek to graze their animals. Pastoral grievances are distinct from those that motivate extremist group violence. However, once violent extremist groups are established in an area, they transform the political context, and local struggles may then become instrumentalized to serve their extremist agenda.

Security forces need to apply a discriminating approach in counterinsurgency efforts that protects exposed communities and vulnerable populations. This requires long-term work to establish more resilience and a sustained presence in isolated areas that easily fall under the control of violent extremist groups. Security actors should resemble community policing where they earn locals’ trust by deterring and punishing criminal activities that increase insecurity.

Invest political capital and financial resources to improve land management infrastructure. Growing population and land pressure in parts of West and Central Africa can be expected to continue into the foreseeable future. Land management infrastructure, such as maps and physical markers, is crucial to addressing these pressures as is generating community adherence to and respect for agreed-upon land regulations. Local conventions addressing land use encroachment and resource use malfeasance carry more weight when community leaders coordinate efforts among traditional, religious, and civil society actors. RECOPA’s achievements in Burkina Faso standout in this regard. Encouraging similar sets of actors to determine jointly an independent and impartial process for determining land governance helps promote the entire community’s stake in decision making. This would include some kind of recourse to law enforcement and security.

RECOPA’s efforts to provide and maintain land management infrastructure also highlight the importance of building local ownership for these processes. This is facilitated by local financing, which in rural settings is aided by the availability of e-finance infrastructure, such as mobile money. As confidence in such initiatives grow, they can help support other infrastructure investments, such as vaccine sites and wells. In addition to strengthening trust, developing this infrastructure establishes designated sites for pastoralists within and around communities. This, in turn, facilitates local planning to reduce the risks of farmer-herder confrontations.

Train local leaders in dispute resolution techniques. In communities where trust and accountability have been degraded over time and intercommunal tensions are high, effective dispute resolution hinges on the restoration of trusted processes and the inclusion of a broad range of community stakeholders. Investing in training for leaders from all segments of society as independent mediators of farmer-herder disputes can help to accomplish this. Such trainings might draw lessons from Alternative Dispute Resolution mechanisms, which function similarly to the effective and inclusive Kabara committees found in Nigeria.13 Facilitators of these trainings focus on mediation strategies, communication dynamics, active listening techniques, cross-cultural competency, consensus building, and how to achieve impartial dispute settlements. Trained mediators stand a better chance of ensuring trust, confidence, and productive communication between parties.

Developing these skill sets in contexts of recurrent farmer-herder disputes will foster peacebuilding and conflict resolution at both the interpersonal and community levels lowering polarization between groups. It may also curb disaffection among youth and other marginalized populations, relieving the perceived need to take justice into their own hands and reducing the potential for violent altercations.

Prioritize building trust between communities and the security forces. Violence mitigation will not be achieved without more trustworthy and effective security interventions. In relatively secure areas, more information should be collected to understand how and when security forces play an effective role in interrupting violence.

Mechanisms should be developed to increase the accountability and effectiveness of security forces, especially in terms of their capacity to respond rapidly to outbreaks of violence. When local communities believe that security forces will respond quickly and in an unbiased fashion, they are much less likely to support extralegal actions when disputes or altercations inevitably occur. Through such responses, security forces would reinforce their unique capacity to stabilize areas and prevent disputes from escalating into wider violence.