The local al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates responsible for thousands of deaths in the Sahel region of sub-Saharan Africa in the past year — namely, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) — are now reportedly coordinating their operations. The emerging cooperation between jihadist fighters so far appears to be centered more on de-escalating tensions, rather than actually merging their efforts. But the worrying development nonetheless could empower the two groups to wreak even more havoc in the already unstable region and expand their influence across even greater swaths of Africa.

The State of Sahel Militancy

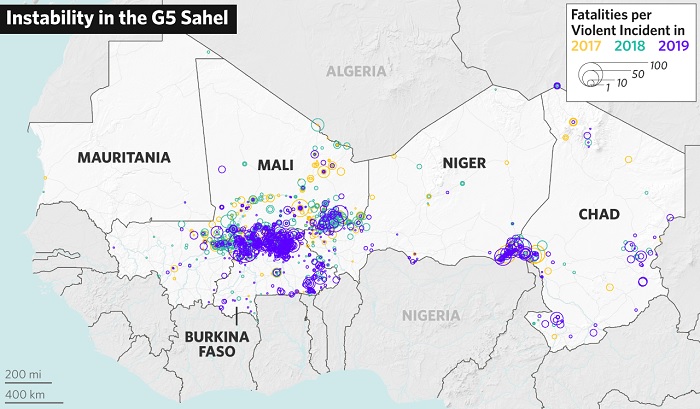

JNIM and ISGS initially operated out of central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Over the past year, increasingly violent and frequent militant attacks have begun affecting the Mali-Niger border area and southern parts of Burkina Faso. Over the past year, more than 2,600 people have been killed and more than a half-million have been displaced in Burkina Faso alone. The surge of jihadist violence is also increasingly encroaching on countries in coastal West Africa. Benin has seen two militant-related incidents along its northern border, including the abduction of two French tourists and an attack on a police post. Meanwhile, other states such as Ghana, Togo and Ivory Coast have ramped up security measures along their northern borders.

The geographic expansion of JNIM and ISGS operations could be a primary reason why the two groups have been able to carry out these attacks without overlapping each other. But the reported collaboration between the two groups could now enable them to exert even more pressure on their common enemies — including the governments of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, as well as international forces such as French troops and the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) — without having to compete over similar areas or resources.

Impact on Counterterrorism Efforts

Amid this new development, actions by JNIM and ISGS will continue to expand and shape the trajectory of the local security environment, as well as the actions of outside actors. High-impact events, such as the collapse of the government of Burkina Faso or the formal seizure of territory by these militant groups (similar to what al Qaeda did in Mali in 2011), would likely prompt the West to devote more troops and resources to counter the growing threat. While less likely than regional attacks, a high-profile transnational attack against a Western country linked to JNIM or ISGS would also likely trigger an even more forceful international reaction. Indeed, U.S. and French officials have warned such a strike cannot be ruled out, given that al Qaeda and the Islamic State have both used other far-flung security vacuums (such as Iraq and Afghanistan) to launch attacks in the United States and Europe. Likewise, a high-profile attack against a neighboring West African country, such as the deadly 2016 shooting at an Ivory Coast hotel, could draw similar backlash, albeit to a lesser extent.

Barring such high-impact events, however, Western forces are unlikely to significantly shift their counterterrorism strategies in the Sahel. A continued slow but steady expansion of coordinated jihadist operations will prompt France will devote more resources to the conflict, but not enough to alter the security environment. The United States, meanwhile, will continue to seek to extract itself from the region as it attempts to refocus its military posture toward great power competition. Should Western powers maintain their current level of support, local governments in West Africa may feel the need to ask for additional help, which could prompt Russia to become a bigger player in the Sahel.

But in the wake of this new development, the actions (or lack thereof) of local governments, especially those in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, will remain the most important in gauging whether this collaboration will enable militants to secure an even stronger foothold in sub-Saharan Africa. Regardless of actions taken by outside players, until these governments are able to address many of the underlying grievances, which they have thus far proven unable and/or unwilling to do, a military response alone will prove insufficient in fending off the growing jihadist threat.

Challenges to Cooperation

Finally, it is worth noting that the reported cooperation between militants in the Sahel does not necessarily signal a broader rapprochement between al Qaeda and the Islamic State. While the groups bear the name of two global jihadist movements, they are almost entirely comprised of local fighters who are primarily concerned with tactical developments on the ground rather than global events. With this in mind, the reported cooperation is almost certainly driven by tactical and operational considerations, rather than ideological unanimity or strategic guidance from the Islamic State and al Qaeda’s cores in Syria/Iraq and Afghanistan, respectively. Both global movements continue to tout their own ideological supremacy and maintain they are the only true global jihadist movement. Likewise, their branches continue to directly compete for influence in other theaters including Afghanistan, North Africa, Somalia, Syria and Yemen, among others.

Just because these groups are cooperating now also does not mean they will continue to do so in perpetuity. Either side could eventually grow restless with their area of operations, resources or propaganda output and seek to subsume the others. Local and even personal rivalries between leaders could also hinder cooperation or cause the groups to turn on each other. But while this development may lessen the external threats the groups pose, many civilians in the area are still likely to get caught in the crossfire of the burgeoning competition.